In focus

The working world of the future requires courage

The world of work is changing radically and rapidly. Who is benefiting from the change and who is lagging behind? Experts from the University of Bern from the fields of sociology, psychology and economics have answers.

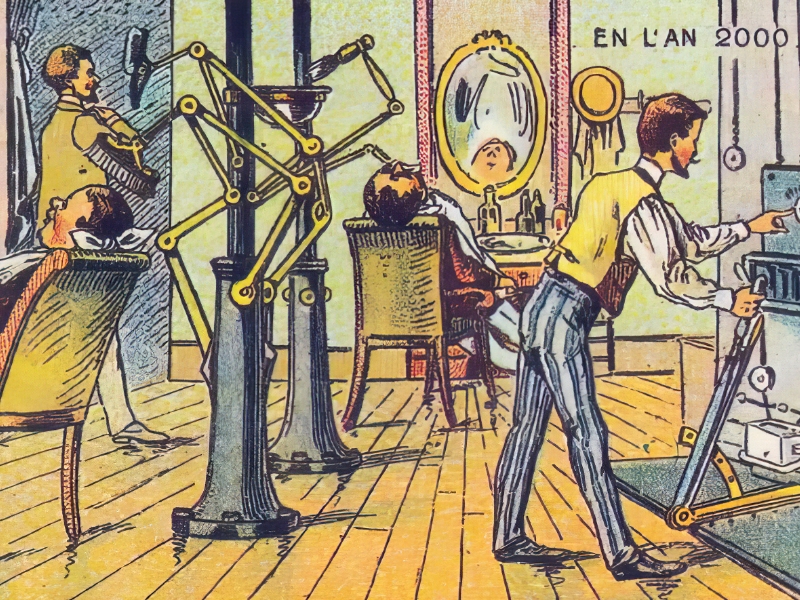

New work, gig economy and work-life balance: These and similar buzzwords bear witness to the transformation of our working culture. At the same time, digitalization, automation and artificial intelligence are changing the way we do things in a very tangible way.

Trend toward shorter working hours

The trend toward shorter working hours is not particularly new, but is becoming increasingly evident: In Europe, Switzerland is one of the countries with the highest number of hours to be worked per week, but also the highest proportion of part-time employees. It is now clear to employers: If they want to attract and retain specific personnel, they must offer part-time and flexible working arrangements wherever possible. Surveys show that many employees in Switzerland want to work less than 42 hours per week.

“Even with a smaller carbon footprint, the level of prosperity can be high.”

Stephanie Moser

The question therefore arises: Why not reduce working hours overall? The question is interesting not least from the perspective of society as a whole, as there is a lot of unpaid work done in private that is relevant to society but difficult to do in addition to full-time employment. “A reduction in working hours could enable a more equitable distribution of the remaining work among employees,” says Stephanie Moser from the Centre for Development and Environment (CDE). This is particularly interesting in view of the loss of jobs due to technological advances. Moser researches the connections between work, income, consumption and well-being. She also explains that, “Countries with shorter working hours tend to have lower carbon footprints.” Studies have also shown that in countries with lower working hours, it is possible to have an equally high life expectancy with lower CO2emissions. “In other words: Even with a smaller footprint, the level of prosperity can be high,” says Moser.

About the person

Stephanie Moser

is a psychologist and heads the “Just Economies and Human Well-Being” research area at the Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), a strategic competence center at the University of Bern.

More satisfaction and less stress thanks to shorter working hours

Stephanie Moser and other researchers recently completed a study at GZO Spital Wetzikon – Zürcher Oberland Health Center. This reduced working hours for nursing staff working on athree-shiftmodel by ten percent. This corresponds to one to two shifts per month. This showed that the satisfaction of nursing staff with their working hours and employer increased noticeably and symptoms of stress decreased. At the same time, the hospital, as an employer, noticed that sick leave decreased and staff turnover fell. Vacancies were also better filled.

Costs remain a challenge

The costs in the experiment did not, however, develop as expected: The savings resulting from lower downtime costs could not offset the effective costs of reducing working hours. “However, other, non-quantifiable costs are not included in this equation,” says Moser. By this, she means, for example, the additional effort in communication and the unrest in the workflow and team that arise when temporary workers have to be deployed on a regular basis. The costs to society as a whole as a result of widespread stress are also reduced due to fewer absences.

Magazine uniFOKUS

The changing world of work

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view. Current focus topic: The changing world of work.

Shorter working hours not realistic everywhere

“However, we must not overlook the fact that reducing working hours is not equally easy to implement in every sector and entails numerous organizational and cost issues for companies,” says Moser. “Particularly when we are talking about a real reduction in working hours with compensation – i.e. employees’ wages remain the same despite fewer working hours.” According to Moser, if wages are reduced with working hours, this could lead to people in the lower income brackets having to do several jobs: “And in the end, they actually work more than before.”

Improved work-life balance thanks to flexibility

Moser advocates thinking further about new models. “We at the CDE are interested in, for example, whether and how the boundaries between traditional paid and other work could be rethought. Not only do we work professionally, we also do a lot of unpaid work that is very important to society. What kind of model could better reconcile these two categories?”

About the person

Ben Jann

is Professor of Social Stratification and heads up the investigations of the national longitudinal TREE study (Transitions from Education to Employment). Among other things, he has published on inequalities in the labor market and gender equality.

More flexible working models meet the growing need for an improved work-life balance. Sociologist Ben Jann sees the results of the TREE study, among other things, as evidence that this demand is becoming increasingly widespread among employees. This study uses long-term surveys to examine the education and employment pathways of various cohorts after leaving compulsory education. Jann also sees increased flexibility as a change in work values and believes that “moving away from a system that requires unconditional sacrifice for your profession is desirable in many ways.” Such a development could also be relevant for gender equality, which still does not exist today in the world of work, says Jann.

A question of distribution

In addition to changes in working culture, the world of work is also subject to technological developments. Today more than ever – and at an unprecedented pace. “The big unknown is clearly artificial intelligence,” says Jann. It is simply not yet possible to gage how this will affect the world of work and thus society, he says. This technological advancement is relevant in almost all professions. So no sector is spared.

“The key question is: How is society dealing with current developments?”

Ben Jann

“The great hope behind this development is that at some point we will all have to work less because the machines do the work for us,” says Jann. It is questionable, however, whether that will happen. “Let’s just suppose that actually does happen: How will these fruits be distributed?” If value added increased overall, the population as a whole could achieve a higher level of prosperity with less (gainful) work. However: “It’s a distributional issue,” says Jann. Some companies stand to gain a lot during the transformation phase, while others will benefit less. If all of the value added goes into a specific area and the remaining 99% of the community gets nothing out of it, then the development will only increase inequality. “The key question is therefore: How is society dealing with current developments?”

For the first time, more jobs are being lost than new ones are being created

The economist Michael Gerfin also sees the current digital development as a phenomenon that cannot be compared with previous developments. Every technological advance in the past saw workers being replaced by machines. But at the same time, new jobs and job profiles were also created. “Until the 1990s, roughly speaking, every job that became superfluous was replaced one-to-one. With the latest wave of digitalization, this no longer seems to be the case,” says Gerfin.

About the person

Michael Gerfin

is a professor at the Department of Economics in the fields of health economics, labor economics and microeconometrics. Among other things, he focuses on misguided incentives in the healthcare system and on healthcare costs.

Although the studies on this are not yet fully developed, it appears that more jobs are actually being eliminated than new ones created. At least that is what happened in the United States. “This will also be a challenge for Switzerland.” Nevertheless, Gerfin stresses that the assumption that there is a fixed amount of work that can be distributed is wrong. “The total amount of work that people can do is constantly changing.” What is new, however, is the speed of this change: “If the pace continues like this, the world of work will be completely different in ten years’ time.”

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

Creativity and humanity remain relevant

What is also new is that activities that had previously been largely unaffected by automation are now also affected. In professions with a high proportion of cognitive work, AI tools can now reduce the number of work steps involved. In order to avoid being completely replaced as employees in these areas, we therefore need to develop strengths in areas AI cannot take over. For example: creativity and innovation. Gerfin reports that this phenomenon can already be seen in the US, using editors as an example. Their number has declined significantly in recent years. Because nowadays, an AI tool can also check spelling and grammar – and do so much more efficiently. As an editor, it is therefore the human skills that count. You have to feel where there are gaps in the narrative, how stringent a style is, what sounds appropriate linguistically. As a result, only really good editors are used. This is what happens at the upper end of the income scale: Highly skilled, innovative professionals do not need to worry about their jobs, while those who perform their duties “by the book”, even though thoroughly and reliably, are at risk.

About the person

Jeanne Tschopp

is an assistant professor at the Department of Economics in the fields of labor economics and international trade. Among other things, she researches how labor market restrictions and the structure of wage formation influence the functioning of labor markets.

At the lower end of the scale, there are also many workers who need to worry less. Those in professions in the fields of nursing, care, therapy, support and personal hygiene. “These areas of work can perhaps be made more efficient with AI in some cases, but the core tasks cannot be replaced in this area.” So little happens at the poles of wage distribution. “The question is what happens to employees in the middle range,” says Gerfin.

A few companies are ahead of the pack – and create more inequality

His colleague Jeanne Tschopp also sees in her current research that growing inequality does not only affect those who are already affected. Wage differentials are widening where new technologies are primarily beneficial for highly qualified employees. Not only in comparison with less qualified employees, but also among those with similar qualifications. Technological improvements primarily benefit particularly productive companies. These are becoming even more productive, growing, paying higher wages and thus attracting more and more highly qualified, established specialists – who then leave other companies. “Over time, this leads to larger wage differentials between companies – including between employees with similar skills,” says Tschopp.

“Wage differentials between companies are increasing – including between employees with similar skills.”

Jeanne Tschopp

Like Tschopp, Gerfin and Jann also see the risk of even greater inequality as a result of current developments. However, both also remind us of how creative people are and that they have always opened up new fields of activity for themselves in the past. “Sometimes it takes a bit of courage and entrepreneurial spirit, but it’s possible,” says Gerfin. And Jann emphasizes: “The changes – even though they are rapid at the moment – happen gradually, from day to day. This allows us humans to adapt. And we’re good at that.”

AI requires everyone to act responsibly

Nevertheless, it is important to respond to developments at a higher level as well. For example, the mechanism described by Tschopp will eventually lead to a concentration of markets and power, says Gerfin. “A few providers will then be able to charge higher prices and, over time, they will also be able to put pressure on wages. And last but not least, they are gaining more and more political influence.” This is what has already happened in the tech sector. “That’s why countries are trying to set limits with competition commissions.” The new developments in the field of AI are also posing new questions for them. “There are people on the committees who have to bear the responsibility. And not only there: In the end, it is humans everywhere who have to act responsibly – including when it comes to using AI.”

The question “How is society coping with the change in the world of work?” is and remains the question that we must ask ourselves individually and negotiate together.