On Labor Day

Trade Unions: Last Dinosaurs or Efficient Support?

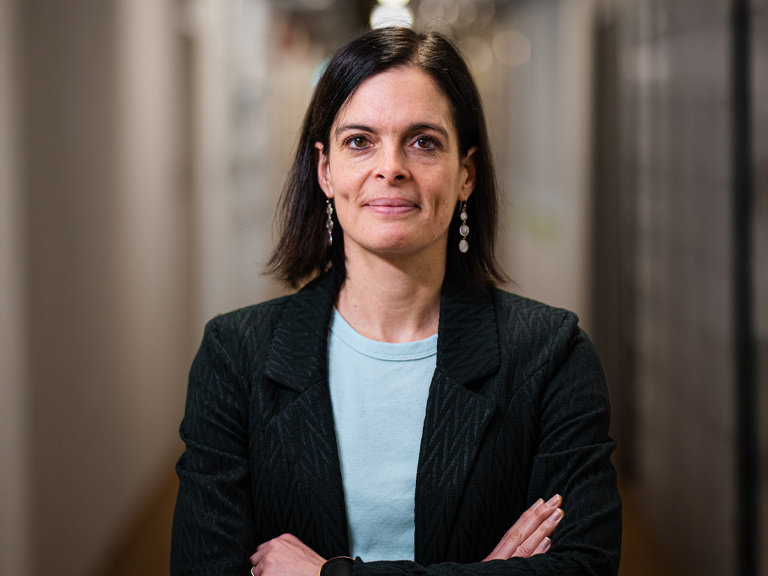

Political scientist Klaus Armingeon is professor emeritus at the University of Bern. In his essay, he shows what significance trade unions still have in 2025, how they might have to modernize and what would be missing without them.

European trade unions emerged during industrialization. They were the economic arm of the labor movement, which wanted to improve often miserable working conditions, with strikes as the last resort in labor disputes. Parties taking on the class struggle were the second, political arm. In their manifestos, they sought to overthrow capitalism.

Today, the working conditions of early industrialization have disappeared, welfare capitalism enjoys widespread support, and left-wing parties have become largely detached from their close ties with trade unions. Have the trade unions become the dinosaurs of the perished industrial age, nestled in Monbijoustrasse in Bern, the headquarters of the Swiss Trade Union Federation (SGB), from where they develop at best useless and at worst even harmful activities?

What do trade unions actually do?

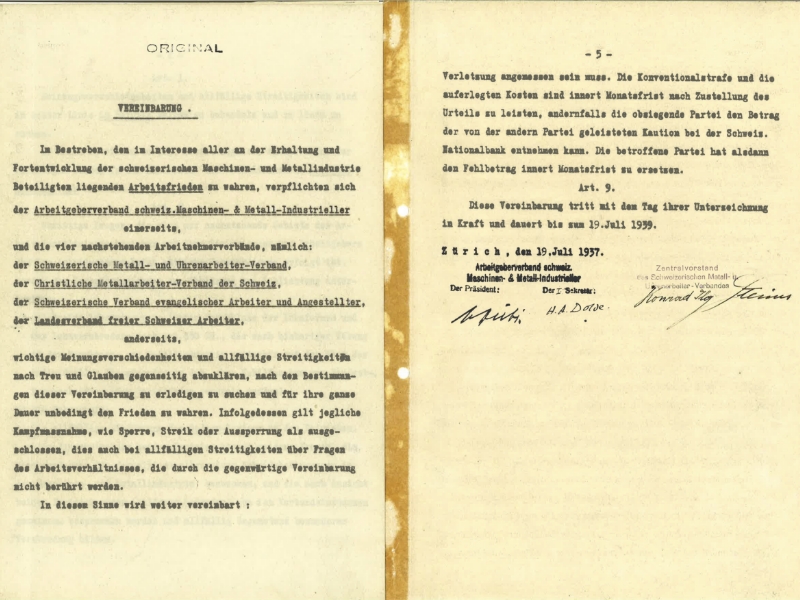

Trade unions are organizations representing the interests of employees. A key instrument is collective agreements (“collective labor agreements”, “collective wage agreements”), in which working conditions are regulated in a binding way with employers. In Switzerland, nearly half of all employees are currently covered by a collective agreement. In this way, employees protect themselves very successfully against wage-undercutting competition. Trade unions also represent the interests of their members in the political process and in public. They also offer training and assistance to their members, manage unemployment funds and participate in numerous public and private institutions.

“Welfare capitalism enjoys widespread support.”

Klaus Armingeon

The boundaries between trade unions and professional organizations are not clear. The Swiss Professional Association of Nursing Staff, for example, does not consider itself a trade union, but performs a trade union’s functions by its very successful political lobbying. Nearly half of all trade union members are in associations affiliated with the SGB, which has historically been close to the Social Democratic Party. 20 percent belong to travail.suisse, a consortium of the former Christian trade unions and the employees’ association; the rest is in other employee organizations.

Do trade unions inhibit innovation?

The work of trade unions is often criticized: If they overshoot the scope for distribution, it will benefit no one, but will drive up prices. They supposedly hamper companies’ ability to adapt to global economic developments by insisting on rules and opportunities for participation. They might even harm their clients’ job interests by stifling job growth, whereas everyone would ultimately benefit from a deregulated labor market: An incoming tide lifts all boats, even those that are small and weak.

On this view, even the weakest in the labor market benefit from great flexibility on the part of companies. Finally, trade union representation in the social partnership, in government institutions and its de facto veto power in many policy areas is said to prevent necessary reforms, for example in pensions or in shaping relations with the EU.

While some of this criticism may be justified, trade unions can point to their remarkable achievements:

- Income inequality is contained by collective bargaining agreements. Countries with weak trade unions, such as the U.S., have seen a particularly sharp increase in income inequality in recent years.

- Collective labor agreements can even stimulate innovation, as companies rationalize away low-productivity jobs whose wage costs become too high as a result of collective wage agreements. In this respect, they contribute to modernization and economic growth.

- Trade unions make it difficult for bosses to pursue a frivolous “hire-and-fire” policy that is harmful in the long term.

- In Switzerland, as in many other European countries, trade unions play a crucial part in solving economic and political problems in a spirit of social partnership. For example, they helped employers cope with the COVID crisis by rapidly agreeing on more flexible rules for short-time work, jointly with government representatives.

- In addition to a moderate wage policy, which ensured a relatively stable share of wages in national income, trade unions have also been able to achieve social policy objectives: For example, they were behind the initiative of a 13th monthly old-age pension payment, which led to an increase in pensions of around 8 percent – but also caused corresponding funding problems.

Modern world of work = death of trade unions?

Modern societies are currently undergoing rapid changes in the world of work. Whereas, in 1960, only just under 40 percent of the workforce were employed in the services sector in Switzerland, this rate has risen to over 80 percent today; manufacturing fell from just under 50 to 16 percent over the same period. Female employment has risen from 40 percent (1970s) to 84 percent today.

Part-time work has increased from a quarter of the workforce in the early 1990s to more than a third today. Migration has increased the proportion of workers without Swiss citizenship to 35 percent of all employees today. Digitalization and the development of platform work have changed the world of work, and along with this came greater individualization – the feeling of belonging to the social group of employees has been replaced by the insistence on personal fulfillment.

“Trade unions have hardly managed to adapt to new working environments.”

Klaus Armingeon

At the same time, the proportion of employees with college degrees has increased. As a result, the trade unions were facing a headwind. They were primarily organizations made up of male, full-time trained workers in manufacturing. They had similar working conditions, and it was less of a problem to identify as a member of the workforce than it is today.

In addition, spatial concentration in larger companies – more so abroad than in Switzerland – has facilitated the organizational conditions for trade unions. But how, in this new world of work, can trade unions reach women, employees in the rapidly expanding services sector, young people with degrees, and workers with platform jobs or working from home, and persuade them to join?

Missed opportunities for adaptation

Trade unions in Switzerland, but also in other European countries, have achieved little in the way of organizational adaptation to new working environments. This was due to objective conditions such as the dramatic changes mentioned, but also to a considerable inertia on the part of the trade union elites, who turned a blind eye to the demise of the industrial age and stuck to their postwar rhetoric, which seemed increasingly out of date.

Added to this, there were problems on the part of employers. International economic ties made it more difficult for companies to submit to the discipline of a national employers’ association and to accept the particularities of national labor relations. Even in countries with a spirit of social partnership, like Switzerland, companies’ willingness to enter into collective agreements and to make compromises weakened.

The changing objective organizational conditions and a failure to adapt the organization to the new world of work caused a crisis in trade union organizations. While, in the late 1970s, nearly a third of Swiss employees were members of trade unions, this share has now dropped to less than 15 percent.

Who then is still a member today?

Theoretically, a growing membership also increases the credibility of the trade unions’ claim to be representative of employees and their leverage vis-à-vis employers and the government, not least with regard to ballot measures and initiatives. Membership numbers also matter for financial reasons, with trade unions being largely funded by membership dues.

The following information is based on analyses of accumulated European Social Surveys (ESS) from 2010 through 2024 for Switzerland. Employees were asked whether they were members of a trade union or similar organization. Key findings include:

- 10 out of 100 respondents said they were trade union members. Peaks of more than 85 percent were recorded, for example, in Sweden in the 1990s.

- The rate of organized labor was much higher among men than women. We know, however, that in recent years trade unions have been increasingly successful in recruiting women.

- There are serious shortfalls in organized labor among employees under 35. This finding is stable across Western Europe and over time. Today, as in the past, employees typically do not join unions until after completing their education or training and establishing themselves in their profession or trade.

- Swiss trade unions greatly depend on people without Swiss citizenship. In some associations, up to half the members do not hold a Swiss passport. Conservative estimates based on the ESS surveys suggest an average proportion of members of significantly more than 25 percent. Thus, as far as elections and votes are concerned, the trade unions can at best mobilize three quarters of their members to go and vote.

- Trade unions continue to have a shortfall of organized labor among office workers and employees in the services sector. Peak rates of organized labor are found among so-called socio-cultural specialists. These include teachers, social workers, healthcare staff, and creatives in the broadest sense. However, at less than 20 percent of employees, this group is too small to become the mainstay of a modernized trade union movement.

Two views

Those who assume that societies and national economies work best when market forces are largely unhemmed in their development and who consider unchecked competition on the labor market as desirable as competition between products will continue to revile trade unions. However, those who stress the value of social cohesion and of negotiated and compromise-driven dialog between social groups will come to a milder and even very positive judgment about trade unions.

In countries like Switzerland, they are pillars of market-correcting politics, counterbalancing the weak position of individual employees on the labor market and ensuring more equality and solidarity. On this view, the obvious organizational problems of trade unions do not give cause for scorn, but for concern: If the trade unions do not succeed in their modernization and organizational consolidation, many western countries, among them and in particular Switzerland, will lose political, social, and economic stability.

About the author

Klaus Armingeon

is a political scientist whose research focuses on comparative political economy, political sociology, and European integration. He works on topics such as social inequality in political participation, the representation of interests by organized labor, the polarization of parties, corporatism, the development of the welfare state, austerity policies, liberalization, and redistribution. In the area of European research, his focus is on the interaction between national welfare states and the rationales and requirements of European integration. He is currently an associate researcher at the Institute of Political Science of the University of Zurich. From 1993 through 2020, he was Professor of Comparative and European Politics at the University of Bern.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

Magazine uniFOKUS

The changing world of work

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view. Current focus topic: The changing world of work

Subscribe to uniFOKUS magazine