Planetary sciences

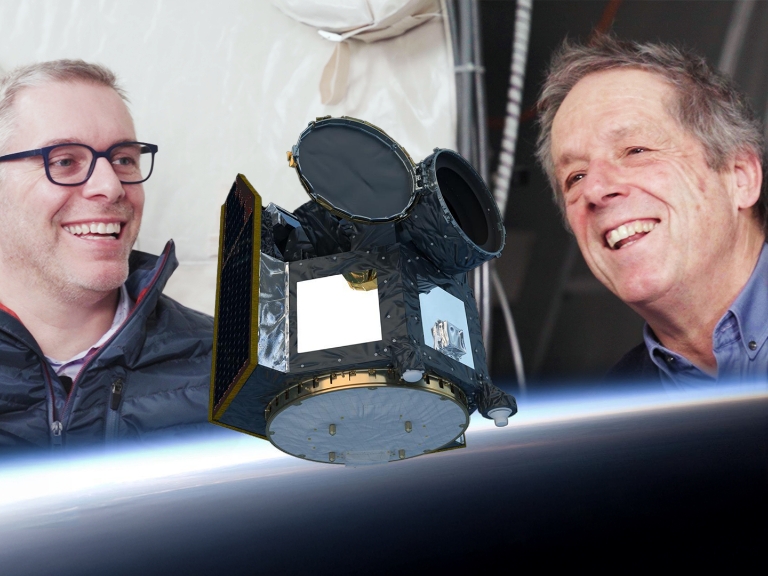

Jonas Kühn captures images of very distant planets

Professor of Astronomical Instrumentation Jonas Kühn has developed a new type of instrument. It is based on liquid crystals, as we know them from smartphones, and will image planets outside our solar system on a new telescope.

On the screen in his office, Jonas Kühn shows a photo that changed his life as a researcher. The picture from 2008 shows three inconspicuous dots - planets orbiting around another star.

It was the first direct image of an exoplanetary system outside our solar system. Previously, such distant worlds could only be detected using indirect methods. "I was overwhelmed," says Kühn. "I found it incredible that it was possible to directly image planets orbiting stars. This was completely novel, and I immediately realized that I wanted to do this too."

Liquid crystals bring the breakthrough

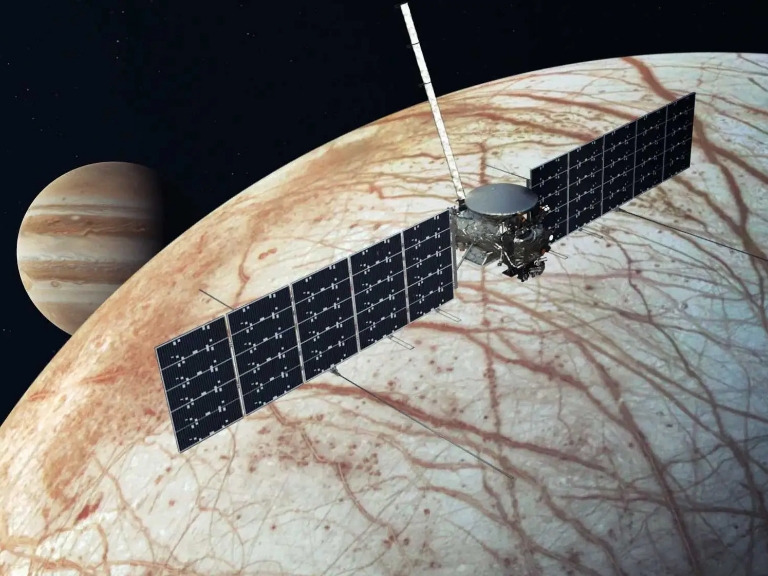

Today, the professor at the University of Bern is leading a project called PLACID, which will enable direct imaging of exoplanetary systems in a completely new way. Direct imaging requires a so-called coronograph – a mask that blocks the bright light of the star in order to make the much fainter planets visible.

Instead of placing a plate very precisely in the light path of a telescope, PLACID uses digital technology based on liquid crystals, as known from the displays in smartphones or computer and TV screens.

"I found it incredible that you could directly image planets orbiting around other stars."

The new PLACID instrument was built jointly by the University of Bern and the University of Applied Sciences and Engineering of the Canton of Vaud in Yverdon (HEIG-VD) and was installed in a new 4-m telescope in eastern Türkiye in 2025. It is scheduled to go into operation in the first semester of 2026.

From the microcosm to the stars

At the time when Kühn was enthusiastic about the first exoplanet images, he was working on a completely different topic. For his doctoral thesis at the ETH Lausanne, he investigated the microscopic world of living cells and microbes. However, because he had always been fascinated by space exploration and astronomy, he got talking to former NASA employees who moved to Lausanne at the time. This gave him the impetus to apply for a postdoctoral fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation, which ultimately took him to the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

"Nowadays, it's rare that you can develop an instrument from scratch, install it in a large telescope and observe with it yourself."

"At JPL, I learned how to build astronomical instruments," says Kühn. However, he not only worked in the laboratory, but was also able to carry out observations with the Palomar 5-m Hale Telescope in California and the 8-m to 10-m telescopes in Hawaii, which particularly fascinated him.

He is already looking forward to the time he and his team will spend at the Turkish observatory. "Nowadays, it's rare that you can develop an instrument from scratch, install it in a large telescope and observe with it yourself," he says: "So I can consider myself lucky."

Digital revolution reaches exoplanets

Kühn had the idea for the new instrument based on his experience with interferometric microscopy, where digital technology had led to decisive advances. "With traditional coronographs, we still use these expensive and hard to manufacture phase plates," explains the scientist. "I want to drive forward the digital revolution in the direct imaging of exoplanets too." With active liquid crystals display panels, called Spatial Light Modulators (SLMs), it is possible to adjust the path of the light for each pixel on a 1 Megapixel screen. This means that very complex masks can be created with a single mouse click, making the life of the observing astronomers much easier.

Kühn was able to demonstrate that this idea works in a laboratory at ETH Zurich in 2017, thanks to a SNF Ambizione fellowship. He has been working at the University of Bern since 2019, where he was appointed assistant professor in 2022. He praises the inspiring environment: "We have something of a mini-JPL here, with highly qualified engineers building space instruments and many small research groups helping each other." Thanks to the internal support, Kühn was also able to win the contract to build PLACID, alongside colleagues from HEIG-VD who are conceiving the adaptive optics system for the Turkish telescope.

Ski lift to the telescope in Türkiye

The newly built 4-meter telescope called DAG is located in eastern Anatolia. "The landscape looks similar to the Jura," says Kühn: "Only we're a good 1000 meters higher there." From the nearest town, Erzurum, it takes in spring and summer 40 minutes and in winter about an hour and a half by car to reach the telescope at 3170 meters above sea level. "During the snow season, first we drive to a nearby ski resort, then take the ski lift further up, where a snow cat picks us up and takes us to the observatory," says Kühn: "It's pretty fun." Over the next few months, he and his team will make several visits to setup the PLACID instrument for operation. Derya Öztürk Çetni from the umbrella organization Türkiye National Observatories says: "We are delighted to be working with Jonas Kühn and his team, and we are excited about the entire PLACID process."

Ruben Tandon, a doctoral student in Kühn's team, has already compiled a catalog of observation targets. Among other things, the researchers want to try to directly image exoplanets orbiting resolved binary stars. "This will be a first," says Tandon. This was previously not possible with conventional coronographs. "With PLACID, we can adjust our mask in real time so that the light from several stars is perfectly blocked at the same time," he explains.

With an ERC Consolidator grant amounting to 2.7 million euros, the researchers at the laboratory in Bern are already working on further developing this technology. They hope that one day such a digital coronograph will be installed in one of the future giant telescopes, such as the 39-m European Extremely Large Telescope in Chile.

Combining research with family life

Kühn is aware that the privilege of being able to work in a remote observatory also has its downsides. "When our first child was born in the USA, my wife often had to manage on her own, and even now I'm frequently away," he says. "In general, it's not easy to reconcile a family and an academic career. If you're doing on-site astronomical observations, it's probably even more difficult."

"In general, it's not easy to reconcile family and career. When you're doing on-site astronomical observations, it's probably even more difficult."

His two sons, aged six and twelve, enjoy watching science fiction movies such as Star Wars. Being naturally curious, they are also interested in their father's work. “Astronomy gives me a big advantage over some other fields of research,” says Kühn. 'When I explain what I do, some people ask what the point of it all is, because we will never get to travel there, but most find it very exciting.'

He would love to take his wife and children one day on a visit to a large observatory so that they can experience the fascination for themselves: "When you watch the dome open and the huge telescope start to move, when the sky becomes visible and all those photons collected from a star appear on your screen: That's something really special."

About

Jonas Kühn

is Assistant Professor of Astronomical Instrumentation at the University of Bern. He develops new concepts for particularly sensitive and high-contrast instruments to directly image faint exoplanets.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Jonas Kühn

Physics Institute, Space Research and Planetary Sciences Division

jonas.kuehn@unibe.ch

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.