Social anthropology

Crowds in a state of intoxication

If you become intoxicated, you risk losing your balance – and that also means your mental balance. It is a frightening and at the same time pleasurable state that humans have always consciously sought out.

Being intoxicated and beside yourself, feeling dizzy and staggering are physical and mental states that can be witnessed throughout the world at celebrations and in ritual contexts. Trance states and ecstatic dances are also part of the intoxicating escapades of “being out of your senses”.

In German, the word Rausch, which means intoxication, is onomatopoetic and suggests rushing and buzzing noises. The Middle High German noun rūsch “noise, impetuousness” and the corresponding verb rūsen “to make a noise, shout, run, race” characterize impetuous people. It was not until the 16th century that intoxication was associated with drunkenness or a fog of the senses as a result of taking narcotics. The extension to mental drunkenness, staggering and ecstasy followed in the 18th century.

As a media anthropologist, I am particularly interested in collective frenzy: Ecstatic states that were not individually and primarily caused by intoxicants, but mass phenomena that cannot be explained solely physiologically.

“In the middle of the summer of 1374 a strange thing arose on earth and suddenly in German lands, on the Rhine and on the Moselle, people started to dance and hurtle around…” is to be read in the Chronicle of Limbach about a mysterious eruption in Aachen. Men, women and children danced around in public squares until they entered an ecstatic state and fell to the ground, unconscious, foaming at the mouth or even dead. More than 80 such events are documented throughout Europe from the Middle Ages.

St. Vitus’ Dance and St. Anthony’s Fire

This is a mass phenomenon which is known as St. Vitus’ Dance or St. Anthony’s Fire . One of many explanations is that the spasmodic muscle twitches that occurred were symptoms of poisoning caused by the ergot fungus, a cereal parasite (see Page 28). Another term is dancing mania or choreomania, a term that originates from choreía, which translates as “dance,” and the concept of mania, known in ancient times as a form of divinely inspired madness or frenzy.

Churches often interpreted choreomania as signs of “possession” or religious hysteria. St. Vitus and St. Anthony became namesakes for these states. For example, when affected byfalling sickness,Vitus experienced epilepsy, convulsions and rabies. Anthony, the hermit, is said to have been haunted by tormenting visions and hallucinations in the desert. Saints and other representations of this “temptation by the devil” were intended to illustrate the torments, and heal or at least comfort those suffering from hallucinations.

“The oldest flash mob in the world”

Probably the best-known choreomania took place in Alsace and went down in history as the “Strasbourg Dancing Plague of 1518”. Described in the English newspaper “The Guardian" as the “world’s longest rave” or the “world’s oldest flash mob” on the Internet, it is said to have been triggered by just one woman. “The creator of this dance was a woman named Troffer, a stiff-necked, unpredictable, great creature who wanted to annoy all people, especially her dear husband, with her absurdity” is quoted in the Historical-literary book of anecdotes and examples. In the following weeks, up to 400 people were struck by this dancing mania. The phenomenon was interpreted as a form of ecstatic religious ecstasy that turned into “mass hysteria”.

One of the first to separate the St. Vitus’ Dance from demonology and the belief in possession and to interpret it as a form of pathology was the Swiss physician and natural philosopher Paracelsus. The authorities in Strasbourg accordingly ordered those affected to continue dancing until they were completely exhausted and practically sweat out the disease. Finally, they were taken to the St. Vitus' Chapel in Saverne, Alsace, where many are said to have come to their senses. Jumping processions such as those in Echternach, Luxembourg, in which participants “jump” through the streets in rows to polka melodies, are reminiscent of such collective choreomania. Today, they are on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

As if stung by a tarantula

In Apulia, Italy, it has been known since ancient times that the bite of the wolf spider causes those affected to jump around wildly, “as if stung by a tarantula”. The fact that people there also assumed that wild dancing would drive the poison out of the body faster, gave rise to the Tarantella, a folk dance in 3/8 or 6/8 time. In my research on the reception and revival of Tarantism images, I also came across reports of women from the 1950s describing their choreomania:

“My dear Signorina,

During the First World War, I went to work in the fields, and while I was working, I felt a strong bite on my leg. Afterwards I couldn’t work anymore, I felt so bad, I went home and for a long time I danced,”wrote Michela Margiotta in 1965 to the Roman anthropologist Annabella Rossi. As a young woman, she had been bitten by a scorpion and suffered as a tarantata – as someonepossessed by a tarantula – a lifetime of fever attacks, fits of rage and epilepsy.

“Ritualized transgressions of boundaries publicly denounced collective grievances such as forced marriages and the suppression of female sexuality.”

Michaela Schäuble

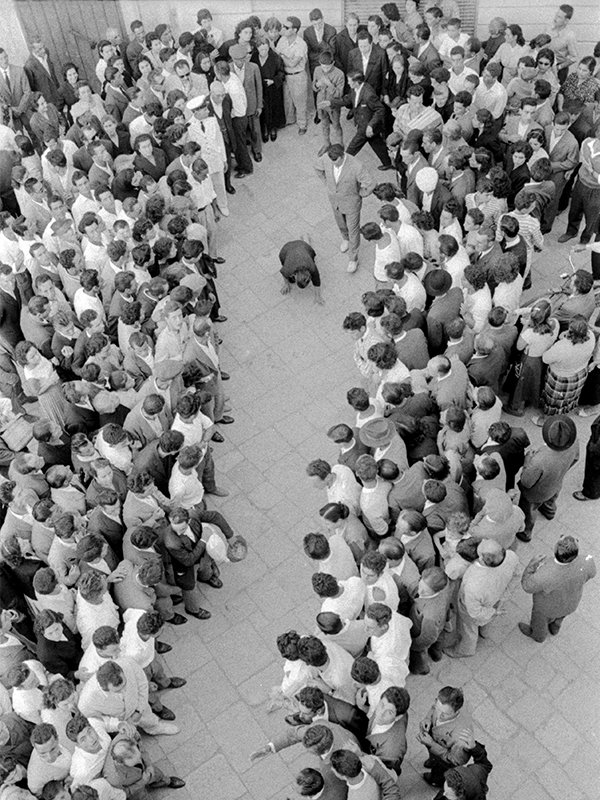

Every year at the end of June, many women, such as Michela, made pilgrimages to the chapel of St. Paul the patron saint of poisonous animals such as spiders and scorpions, in Galatina, to implore him for mercy and healing. In front of and in the chapel, ecstatic and transcending behavior occurred time and again: Women climbed the altar, fell into a trance, verbally abused the saint, or urinated in the chapel. Anthropologists and historians of religion see Tarantism as a relic of ancient Dionysian cults that have been transformed by Catholicism and have survived time. Very often, these ritualized transgressions of boundaries see the public denouncement of collective grievances such as patriarchal structures, forced marriages, oppression of female sexuality and experience of violence.

Even today, believers make a pilgrimage to Galatina at the end of June, asking for healing, especially for mental illnesses. Independently of this, a “Club per l’UNESCO” in Galatina organizes annual reenactments in which film footage from the 1950s and 1960s of the frenetic dances in the Chapel of St. Paul are recreated. While some criticize public performances of mostly female suffering as a tourist attraction or folklore, others speak of a reappropriation and revaluation of their own history. What was once stigmatized as frenzy, falling sickness or uncontrolled intoxication has today become part of Apulian cultural heritage and a productive way of dealing with psychosocial tensions.

In Apulia, pesticides and climate change are blamed for the disappearance of poisonous spiders and thus the absence of “authentic” Tarantism. Other narratives say that today’s environmental poisons or drugs and psychotropic drugs replace the spider’s poison and have a toxic and intoxicating effect.

Overly intoxicating dances and collective out-of-yourself states have always been interpreted as symptoms of “madness” and described with pathologizing terms such as madness, mania or hysteria. Very often, what is considered strange and therefore threatening was and is regarded as sick. In other words, if non-normative behavior creates a stage and thus makes itself heard, it can mean an agonizing and pleasurable breaking away from social norms – and can be experienced as empowerment or crisis management. In southern Italian Tarantism performances today, besides individual sufferings and experiences of violence, socio-political and ecological emergencies are still publicly addressed.

Auch heute noch pilgern Gläubige Ende Juni nach Galatina und erbitten Heilung, vor allem für psychische Erkrankungen. Unabhängig davon organisiert in Galatina ein «Club per l’UNESCO» jährlich Reenactments, in denen Filmaufnahmen aus den 1950er- und 1960er-Jahren von den frenetischen Tänzen in der Kapelle von San Paolo nachgestellt werden. Während manche die öffentlichen Aufführungen meist weiblichen Leidens als Touristenattraktion oder Folklore kritisieren, sprechen andere von einer Wiederaneignung und Umbewertung der eigenen Geschichte. Was einst als Raserei, Fallsucht oder unkontrollierter Rausch stigmatisiert wurde, ist heute Bestandteil apulischen Kulturerbes und eine produktive Form des Umgangs mit psychosozialen Spannungen geworden.

In Apulien werden Pestizide und Klimawandel dafür verantwortlich gemacht, dass es keine Giftspinnen und daher keinen «authentischen» Tarantismus mehr gibt. Andere Narrative besagen, dass heutige Umweltgifte oder aber Drogen und Psychopharmaka das Gift der Spinne ersetzen und eine ebenso toxische wie berauschende Wirkung hätten.

Allzu rauschhafte Tänze und kollektives Ausser-sich-Sein werden seit je als Symptome von «Wahnsinn» gedeutet und mit pathologisierenden Begriffen wie Verrücktheit, Manie oder Hysterie bezeichnet. Sehr oft wurde und wird dabei das als krank angesehen, was als fremd und damit bedrohlich gilt. Wenn sich nicht normatives Verhalten also eine Bühne und damit Gehör verschafft, kann dies ein ebenso quälendes wie lustvolles Ausbrechen aus gesellschaftlichen Normen bedeuten – und als Ermächtigung oder Krisenbewältigung erfahren werden. In süditalienischen Tarantismus-Aufführungen werden heute jedenfalls noch immer neben individuellen Leiden und Gewalterfahrungen auch gesellschaftspolitische und ökologische Notstände öffentlich thematisiert.

About the person

Michaela Schäuble

is Professor for Social Anthropology with a focus on Media Anthropology at the University of Bern and co-founder of Ethnographic Mediaspace Bern. She researches trance states and religious cults. Her essayistic documentary “Tarantism Revisited” (co-authored with Anja Dreschke) is currently in post-production.

Magazine uniFOKUS

Subscribe free of charge now!

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view.