Making the scientific community more inclusive

Since the beginning of the year, Hugues Abriel has been the new Vice Rector for Research at the University of Bern. One of his goals is to bring about a cultural change at the University of Bern. He explains what this means to him in an interview.

You had an intense start as Vice Rector Research: the initiative to ban animal experiments, the first concrete effects of Switzerland's exclusion from the Horizon Europe research program, and now the war in Ukraine - with catastrophic consequences for researchers and scientific cooperation. How does this affect you?

Research and science are things that should unite us. But with the war, we can no longer communicate or work with colleagues from the areas affected. This also affects me directly: I am worried about a colleague’s family in Ukraine; and with a colleague from Russia, with whom I have been working for a long time, our collaboration is extremely difficult because of the sanctions. It's a balancing act. It’s right to sanction the Russian government politically and economically, but I would like to see a door remain open in academia and for us not to completely disconnect from each other like it was during the Cold War.

You are a member of the Ukraine working group at the University of Bern, which was formed in the first days of the war. What can the University of Bern do?

We are teachers and researchers and have to take responsibility for this. The working group consists of people who either have important functions at the University or are directly affected. This includes experts who know a lot about the history and aspects of this conflict and can put what is happening in perspective. Their expertise is very much in demand at the moment, because there is a lot of misinformation and self-appointed experts, especially in social media. So, we provide knowledge. Currently, we are just dealing with the refugee students. There are already 15 who are entering the current semester on a provisional basis. We don't know how many more will come, and the vast majority are women. We have to find solutions for them so that they can continue their studies. And although the situation is acute now, we in the group must also think in the long term.

What does it mean for researchers from Ukraine, Belarus, or Russia when they have to leave everything behind and flee?

For them, like everyone else, it's a matter of survival, and they too have to start essentially from scratch. They have to leave their country because everything has been destroyed or because they can no longer make sense of what is happening. As researchers, it’s like they no longer have a past, but only themselves. We have stories of doctors who have to work as cleaners in Switzerland. If one has the opportunity to help, one has to do it.

Another big issue that concerns you as Vice Rector for Research is Switzerland's exclusion from the Horizon Europe research program. Among other things, researchers in Bern have had to relinquish their leadership of Horizon projects, or decide whether to turn down their ERC grants or move to an associated university. What does this mean for Bern as a location of research?

The University of Bern, like all universities, does not want borders for research, but wants to collaborate with everyone. We have a lot of collaborations in the USA or England, for example, but also with neighboring countries like Germany and France. The current circumstances make cooperation enormously difficult. We have much more paperwork, and it is much more difficult for our partner institutions to involve researchers from Switzerland who would be needed for projects. One Bernese researcher has left us and moved to an Italian university. Universities are competing with one another. And we are now clearly at a disadvantage.

What impact will this have in the long term?

It’s difficult to say. More than 60% of the researchers who receive ERC grants in Bern are not from Switzerland. The fact that we are so international has been an enormous added value for our university so far. We are very attractive to foreign researchers for several reasons. It may well be that this will no longer be the case in the future, and we will only conduct research with Swiss scientists - but that will not be enough to maintain our top global ranking in research.

How do you counter the opinion that the EU is not needed, that the University of Bern should instead collaborate more with universities in the USA or Asia?

That is not comparable with what we are doing now. So far, we have done very well with our neighboring countries and others in the EU. In addition, with the EU grants we have brought a lot of money, among other things, into Switzerland. It is much more difficult to obtain funding from other countries. Namely, in the USA, funding is rarely awarded outside the country. These collaborations cannot simply be replaced. Moreover, this would mean enormous effort compared to how we participate in a giant program that spans the entire European continent.

Speaking of international collaboration: You spent a sabbatical in Kinshasa and Fez and are involved in collaboration with researchers and doctors there. What do you want to achieve with this?

We still have a lot to learn in the field of biomedical research. For example, genomic diversity has been massively neglected in Africa. 98% of studies investigating the causes of genetic diseases are conducted with patients from the West - mostly Europe - and a few with patients from Asia. Only 2% of studies involve people from Africa. If we collaborate with our African colleagues to do studies in African populations, we could learn an enormous amount about the origins of genetic diseases worldwide. This is just one example of the huge potential such collaboration would bring.

Another aspect which is also very important to me, is that I would like to see science and research become fairer. We in Switzerland and Europe have a lot of research funding and are privileged, but during my sabbatical and also previous trips, I noticed that there are thousands of young researchers who are doing exactly the same thing as we are. They are asking the same questions, but have almost zero support. We can definitely make a global impact there, for example by being a member of The Guild, the network of research-intensive universities in Europe.

What would you like to achieve as Vice Rector for Research at the University of Bern? What is important to you?

I think our identity as a research-intensive university is important, and that’s also why we are a member of The Guild. And that we, as a complete university, can work in an interdisciplinary way and conduct "out of the box" research. But it seems to me even more important - and we saw this during the COVID-19 crisis - that our community and the way we do research is changing. Certain concepts that were important in the past are becoming less important, such as the idea of publish or perish, or quantity over quality in publications.

Now people are looking at things a little differently. A group from the University of Bern has launched the "Better Science" initiative, which is supported by Swissuniversities and which I very much endorse. We have to look at what is important to us, what are our values? These should be quality and relevance - and perhaps a little less glamour and quantity. So, I think it's okay if we are less featured in the so-called "CNS journals" (Cell, Nature and Science). We also need to ask ourselves how we evaluate researchers and their work: there is the DORA declaration, which evaluates the performance of researchers according to new criteria. It is very important to me that we implement this at the University of Bern and declare, it is not important where you publish, but that you make a contribution to our society and produce new knowledge.

What advice do you have for young researchers in this regard?

On the one hand, that they apply new rules and, for example, publish their research results as preprints that have not yet undergone peer review by a publisher. In various disciplines, it almost no longer matters what is published where - if a paper provides an important insight, the scientific community immediately recognizes it. Of course, the quality of the paper must be the same as if it were submitted to a journal. So the quality certainly does not suffer.

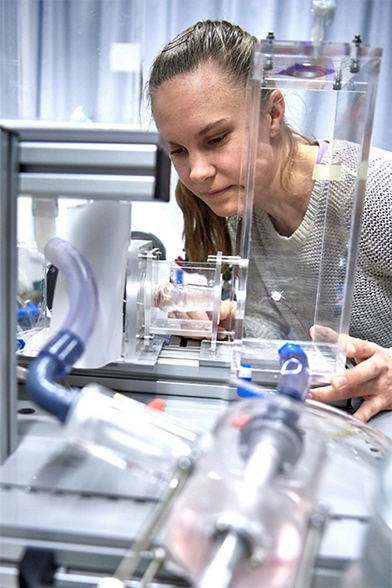

But I think it is even more important to be multidisciplinary and polyvalent. We will only be able to answer the really big and pressing questions if we work together with other disciplines. In our NCCR TransCure, of which I am still director, we combine chemistry, structural biology and physiology. So we try to bring at least tri-disciplinary research to our PhD students and junior researchers.

Are you aiming for a cultural change with "Better Science"?

Yes - and in doing so, we are adopting values and priorities from a society that is undergoing change. Because we are also part of it. For example, I don't agree with the idea of being a very competitive academy which makes individuals sick. So, part of the Better Science initiative is not just that we become fairer, but it's also about taking care of our own people, making sure they feel good and can work in a healthy environment.

Moreover, with these values, it's not just diversity that's important, but also inclusivity. This often means gender, but it also includes social inclusivity. I am an example of this because I am “first gen”, as they say in the U.S. I’m the first generation in my family to go to university. I come from a family where no one went to university. There are not many of us in Switzerland. Many who study come from a family with an academic background. Here, too, one can make an impact. My point is, you can make it, even if you come from a simple working-class background.

What are you looking forward to in your department?

Personally, I have to say, I'm taking a medium- to long-term view. I would like to do my job for eight years and become emeritus. And when we succeed in bringing about a culture change, as "Better Science" suggests, and implementing the DORA principles - then we will have done it. Then we will be a modern, fair and attractive research institution. I would see that as very favorable. If we had further internationalization to go with it, especially with African universities, I would also welcome that very much.

Panel discussion about "Better Science"

On June 9, 2022, a panel discussion will be held at the University of Bern on the topic of "Good Research Culture as Basis for Excellence" as part of the Better Science Initiative, with the participation of Vice Rector Hugues Abriel.

For more information see: www.betterscience.ch/agenda.

About Hugues Abriel

Hugues Abriel is a trained biologist (ETH Zurich, 1989) and physician (University of Lausanne, 1994). He completed his PhD in medicine and natural sciences (specializing in medical physiology) at the University of Lausanne in 1995. After two years of clinical training at the CHUV in Lausanne, he became involved in biomedical research, specializing in the role of ion channels in human diseases.

Since 2009, Hugues Abriel has been Professor of Molecular Medicine at the University of Bern. He headed the Department for BioMedical Research between 2009 and 2016, when he became Director of the Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine at the Faculty of Medicine (2016-2017). Since 2015, he has also been the Director of the NCCR TransCure, based at the University of Bern. From 2012 to 2020, he was one of the members of the Research Council of the Swiss National Science Foundation, and from 2018 to 2020, he chaired the Biology and Medicine Division.

Hugues Abriel is particularly interested in the molecular and genetic aspects of medicine. He has been in close contact with young doctors and researchers from French-speaking Africa for several years and spent an academic sabbatical at the Universities of Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo) and Fez (Morocco) in 2021. He has been Vice Rector for Research at the University of Bern since the beginning of 2022.

About the author

Nathalie Matter works as an editor at Media Relations and is responsible for the topic "Health and Medicine" in the Communication & Marketing Department at the University of Bern.