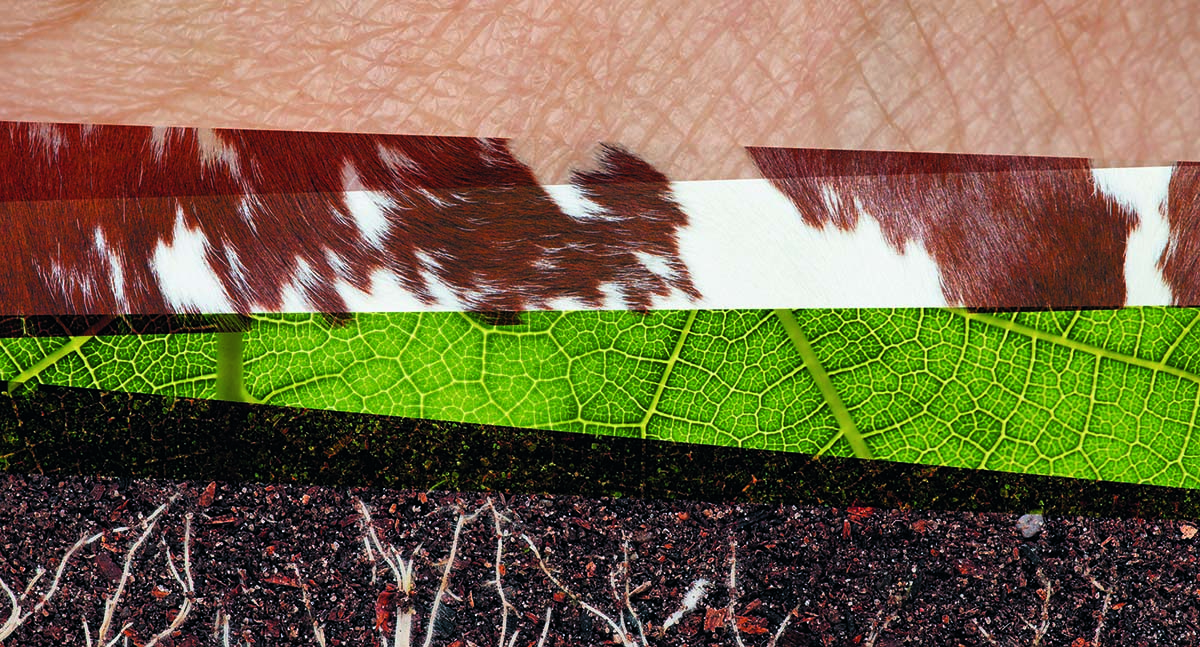

«One Health»

For healthy soil, plants, animals – and people

One Health is an approach that links the health of humans, animals and the environment. What sounds a little esoteric is a term from scientific circles that operate more with hard facts than with subtle vibrations.

How do environmental chemicals affect microbial communities in the arable soil and in the digestive tract of animals and humans – and thus affect their health? This question is at the heart of the interfaculty research cooperation One Health at the University of Bern. The comprehensive and networked One Health approach was first described in 2004. Since then, it has become increasingly important. This is probably also due to the coronavirus pandemic. The leap of the virus from an (as yet unknown) animal to us humans made a large part of the population more aware of the increased vulnerability of our modern society.

Healthy food from a sustainable environment

The interfaculty research cooperation One Health has been in existence since 2018 and is led by plant biologist Matthias Erb and gastrointestinal specialist Andrew Macpherson. Together with their colleagues from a total of nine different research groups, they use an interdisciplinary approach to paint a picture that does justice to the complexity of agricultural production systems and the manifold aspects of healthy nutrition.

“The focus is on how environmental chemicals affect the health of soil, plants, animals and humans,” says Erb. Microbial communities, i.e. the tiny creatures found everywhere in the soil, on plants and in the intestines of animals and humans, play an important role. They are influenced by potentially toxic substances – such as arsenic, pesticides and certain plant metabolites – and thus determine the health of living organisms along the food chain.

“Two hundred years ago, there was no chemical industry. Today, we are exposed to many more different substances,” says Macpherson. “At the same time, the number of people suffering from chronic bowel inflammation has increased,” he adds. These long-lasting and painful symptoms are usually associated with a change in the composition of the intestinal flora, even though the causes of the symptoms are often unknown, with people in the dark about their origin.

Unique starting position

With their interdisciplinary approach, the experts from microbiology, environmental sciences, plant and animal health, bioinformatics and human medicine involved in OneHealth want to shed more light on this darkness. Macpherson points out the unique starting position at the University of Bern, where exactly the infrastructure and specific know-how are available that are needed for the success of their project.

In their work, they have already come across all sorts of exciting results, says Erb, citing as an example the insights that the One Health consortium has gained about a group of substances known as benzoxazinoids. These metabolic products are important for plant health, because with the benzoxazinoids, corn and wheat plants protect themselves against insects, for example by making it difficult for the insects to digest the plant leaves.

“We investigated whether the substances have a negative impact not only on insects, but also on cows who consume these substances via corn silage,” says Erb. This does not seem to be the case: Milk yield and quality, for example, remain the same, says Erb. Of course, the One Health consortium was also interested in the effects of these substances on microbes in the human digestive tract. It was shown that the substances positively influence the composition of the microbial communities. “We are now investigating the therapeutic potential of these promising results,” says Erb.

“We like mechanisms”

But plants use the benzoxazinoids not only to defend themselves against predators. “The substances are also active in the soil,” says Erb. They suppress certain bacteria and fungi that live underground and at the same time attract bacteria that promote plant growth. The research consortium has discovered that the benzoxazinoids excreted by corn plants also affect other plants: For example, they contributed to the increased yield of wheat, which the researchers planted on their experimental field after the corn harvest.

“The principle of crop rotation has been known in agriculture since the Middle Ages,” says Erb. “And we’ve known for a long time that wheat thrives well if you grow it after corn.” But now they have found a new explanation for this observation, a mechanism. “We like mechanisms,” says Erb.

Researchers are forced to focus on individual aspects of environmental health during their expeditions. “There are countless chemical structures in the environment. We have picked out a handful of important substances – and are now investigating their effects in greater depth,” says Erb. But despite this narrow selection, Erb and Macpherson explain that the consortium’s work encourages researchers to think outside the box and beyond the confines of their own discipline.

For example, many One Health researchers are engaged in similar tasks, such as identifying and characterizing the many types of bacteria, viruses and fungi that live in the experimental field or in the animal or human intestines. However, because the samples were purified differently at the beginning, it was not possible to compare the data sets of the different research groups.

Joint method development

Scientists also had to gradually come together in the fields of bioinformatics, dealing with the massive amounts of data and the statistical traditions of translating biological systems into mathematical models. “In regular discussions, we gradually aligned our different approaches,” says Erb.

This joint method development has opened his eyes, says Macpherson. He mentions a recent examination he and his team performed on a patient with an artificial bowel. “We wanted to see how the gut flora changes over the course of the day after breakfast,” says the gastroenterologist.

“After a few hours, we found signals that can only be explained by the patient’s use of cannabis,” says Macpherson. Without the work in the One Health consortium, he and his team would not have been able to see such signs. Previously, they only focused on the microbes in the intestine, but now they can detect many more things, including the genetic traces of plants they eat.

Erb also confirms that his research horizons have expanded as a result of his tasks in the consortium. However, he has also observed that the interdisciplinary approach has an impact on the thinking of the young scientists who carry out the lion’s share of the work arising in the different laboratories.

The seed is growing

With the establishment of the interfaculty research cooperation One Health and attractive teaching opportunities (see the “Health detectives” box), they have made the soil fertile, says Erb. And now young scientists are working on exciting project ideas to ensure that the seeds grow – and that the One Health consortium opens up thematically and takes on new questions. For example, the research groups led by Christelle Robert and Stephanie Ganal-Vonarburg recently joined forces to study the effects of plant hormones on microbial diversity in the human intestine and human health.

While science to date has only been interested in whether or not a certain substance passes through the food chain, Erb explains that the One Health consortium has developed a new perspective with which the researchers want to understand the effects of a substance on the different stages of the chain. This is another reason why both Erb and Macpherson have a positive assessment of what has been achieved so far.

Macpherson explains that thanks to the consortium, he has established contacts that will continue even after the end of a project. “I now know who to turn to if I have a question about heavy metals.” In addition, the gastrointestinal specialist emphasizes the added value that results from different experts being able to contribute their own strengths. “It’s a bit like having a patient: I know where my expertise lies. But I also know when to involve someone else, such as a neurologist.”

Changing your diet

Erb says: “The One Health aggregate is compelling. All the indicators – in the promotion of early career researchers, in publications and even in patents – attest to the excellent basic work of the consortium.” Have the findings also led to specific adaptations in agricultural or medical practice? “You’ll have to ask us again in ten years,” Macpherson replies.

Today, however, the two have already made some changes to their diet due to their participation in the One Health consortium. “I pay more attention to where the food comes from,” says Macpherson. “I try to avoid food that gets here by plane – and I don’t buy avocados anymore.”

And Erb says: “As a scientist, I have now been able to see that it makes a difference whether I drink apple juice or eat an apple.” The dietary fibers in the unprocessed fruit are very important for the absorption of substances from the environment. But apart from that, his intense preoccupation with the multifaceted interactions of living beings in the food chains has also raised his awareness that eating is not just about whether it makes us healthy or ill. It is also worth acknowledging the fact that we are influenced by food in many subtle ways.

Innovative teaching

Health detectives

The interfaculty research cooperation One Health is aimed at young researchers from all over the world with so-called Summer Schools – i.e. one-week block courses in August that are held every two years on a different topic. In 2019, the participants were able to find out about the challenges and future prospects of different food production systems. Or, last year, when the summer school was held online due to the pandemic, they learned about important relationships between soil, plant, animal and human health in different agricultural ecosystems. And in a playful way, because the participants acted as health detectives who had to find out why a farming family had fallen ill.

About the Author

Ori Schipper

is a trained biologist – and writes about research as a science writer and science journalist. He is often just as interested in the approach as the results.

New magazine uniFOKUS

Subscribe free of charge now!

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the new University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS shows what academia and science are capable of. Thematically, each issue focuses on one specialist area from different points of view and thus aims to bring together as much expertise and as many research results from scientists and other academics at the University of Bern as possible.

The online magazine of the University of Bern

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

The University of Bern conducts cutting-edge research on topics that concern us as a society and shape our future. In uniAKTUELL we show selected examples and introduce you to the people behind them – gripping, multimedia and free of charge.