«An information battle we simply cannot afford to lose»

Psychology professor Stephan Lewandowsky examines how dis- and misinformation spread and how they change our societies eventually. On Wednesday, 11 September, he’ll hold a public keynote at the conference of the Swiss Psychological Society at the University of Bern. In this interview he explains what we can do in times of «fake news» to fight disinformation.

uniaktuell: Lies about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq in 2003, the influence of Russia in the US elections 2016 or Donald Trump who isn’t too particular about facts: Did dis- and misinformation increase in the last few years?Stephan Lewandowsky: There has arguably been an increase in disinformation online, to the point where there is now evidence that «fake news» are agenda-setting. However, what I think is more important is a distinct shift of the type of misinformation: From being carefully curated, such as the Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, to being disseminated with great insouciance. Examples for the latter are Donald Trump or Brexit: Whereas Tony Blair and George W. Bush laid claim to reality, Boris Johnson and Donald Trump apparently could not care less if their lies are called out. People of their ideological caliber quite overtly say that «truth isn’t truth» or that «facts are an antiquated concept». This insouciance combined with a blizzard of disinformation has completely shifted the public discourse.

The internet helps a great deal. In addition, it helps to have compliant media that decline to hold politicians accountable as is for example the case in the UK. Furthermore, it also requires a large share of the population being willing to accept lying politicians – and vote for them.

What is the goal of people spreading misinformation?It used to be to convince people of something – for instance that there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. These days, the goal is more to undermine the very notion of an attainable truth itself. Once people lose faith in the concept of truth, democracy becomes impossible because everything is just a matter of screaming the loudest.

What effects does dis- or misinformation have on our societies? Are there cultural differences for instance between the US or European countries?In the US dis- and misinformation have led to the point where people no longer care much about whether or not politicians lie. We have shown that to be the case in a number of studies. In other countries – I have only looked at Australia –, this is not (yet) the case.

People may remember a correction and they may update their memories for those facts. But that unfortunately doesn’t mean that they forget the original disinformation altogether. On the contrary, there is plenty of evidence that people – ironically – continue to rely on information they know to be false.

In times of information overload: How can we as individuals cope with dis- and misinformation?I think we need to be aware of the fact that there are people who want to misinform us, and we need to learn the way in which this is done.

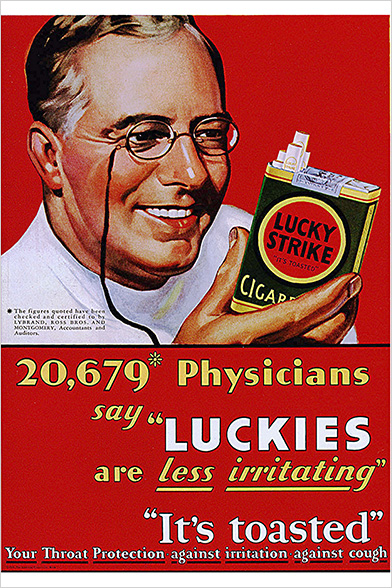

You say people can be vaccinated against misinformation: How can this be done?This is called inoculation and tends to work reasonably well. Inoculation theory proposes that people can be «inoculated» against misinformation by being exposed to a refuted version of the message beforehand. For example, if we show people an ad from the 1950s with a doctor saying «I smoke Luckies because they are toasted and better for my lungs», nowadays, people will say this is utter non-sense. If we then tell those people that politicians lying about climate change do the same and use fake experts, they will be less impressed by climate change sceptic messages. Just as vaccines generate antibodies to resist future viruses, inoculation messages equip people with counterarguments that potentially convey resistance to future misinformation, even if the misinformation is congruent with pre-existing attitudes.

We need to pledge to ourselves that we must be careful in checking information before sharing it. At the heart of democracies is the notion that citizens must contribute to the common good as a civic duty. Today, our civic duty is to resist «post-truth» society and combat «fake news» since the truth is threatened by practitioners of disinformation and deception. In particular, journalists are in the front line in the battle against disinformation and should fulfill their civic duty of telling the truth. But we all must do our parts: We can make it our civic duty to warn our friends, co-workers or neighbours about the dangers of spreading disinformation – the 21st century equivalent of clearing snow from the path of your elderly neighbour should be preventing your neighbour believing every outraged headline. This civic duty becomes more urgent every day since false information spreads fast. Naturally, it always requires people to spread it. So before sharing anything on social media, do some fact-checking. This means protecting your own rights and freedoms – everybody can become an investigative journalist from the comfort of their own laptop. If we value the freedoms we currently enjoy, we should recognize that we are in an information battle which we simply cannot afford to lose. This is our new civic duty.

About the Person

Psychology professor Stephan Lewandowsky is a cognitive scientist with an interest in computational modeling at the University of Bristol. He tries to understand how the mind works by writing computer simulations of our memory and decision-making processes. Recently, he has become interested in how people update their memories if things they believe turn out to be false which led him to examine the persistence of misinformation in society, and how myths and misinformation can spread. He is particularly interested in the variables that determine whether or not people accept scientific evidence, for example surrounding vaccinations or climate science.

Stephan Lewandowsky will hold the public keynote on September 11, 2019, at 5.15pm at the 16th SPS SGP SSP Conference in Bern.

Contact:

Professor Stephan Lewandowsky

Chair in Cognitive Psychology, School of Psychological Science

University of Bristol

16th SPS SGP SSP Conference in Bern

Psychological research makes many important contributions to society – including advancing responsible decision making and action, supporting development throughout the life span, improving healthy living and personal strengths, as well as peaceful living together across diverse groups and ethnicities. The 16th conference of the Swiss Psychological Society will bring together researchers from the various areas of psychology to exchange their newest findings. The theme of this year’s conference «Psychology’s Contribution to Society» will highlight how basic and applied psychological science can add to successful societal development. The goal of the conference is to show how psychological research can make a difference.

About the Author

Lisa Fankhauser is an editor at the University of Bern Communication & Marketing Office.