Sports science

“We watch how muscles grow during sport”

For research purposes, sport scientist Sascha Ketelhut makes test persons sweat and sometimes even play computer games. The passionate sportsman often has ideas for projects while he is out doing sport himself.

Sascha Ketelhut: Well, I am passionate about sport myself. And my interest in sport gave me the idea of turning my passion into my job. I started out in athletics and during training I always asked myself: Why do you train one particular aspect in a certain way and not in a different way? Why do some people swear by certain training content and others don’t – and what are the effects of these different approaches?

Can you investigate these questions in your research?Yes, because our research is very practice-oriented. Like myself, a lot of sport scientists have a personal connection to sport. And that’s why the ideas for research projects often come from practice. The subdisciplines in Sport Science are widely spread and range from Sports Psychology and Sport Pedagogy to Sport Medicine. We focus on human beings, a complex being as everyone knows. To be able to investigate human beings in interaction with the environment, you have to take lots of things into account which necessitates an interdisciplinary approach. This diversity means we are constantly having to think outside the box.

How do you collect your data?The research methods vary considerably depending on the area. While sport psychologists often work with questionnaires, I collect physiological data in the health sciences sector in the lab. I want to use this data to find out what happens in and with our bodies when we move. A device I almost always use in my investigations is a heart rate monitor: The heartbeat is the central indicator to be able to assess the strain and stress on the body and make it visible.

What other instruments do you have in your lab?Along with various sports devices, such as treadmills and bicycle ergometers, we have various measuring systems to make physiological reactions in the body visible, for example heartbeat, blood pressure, oxygen consumption and metabolic rate.

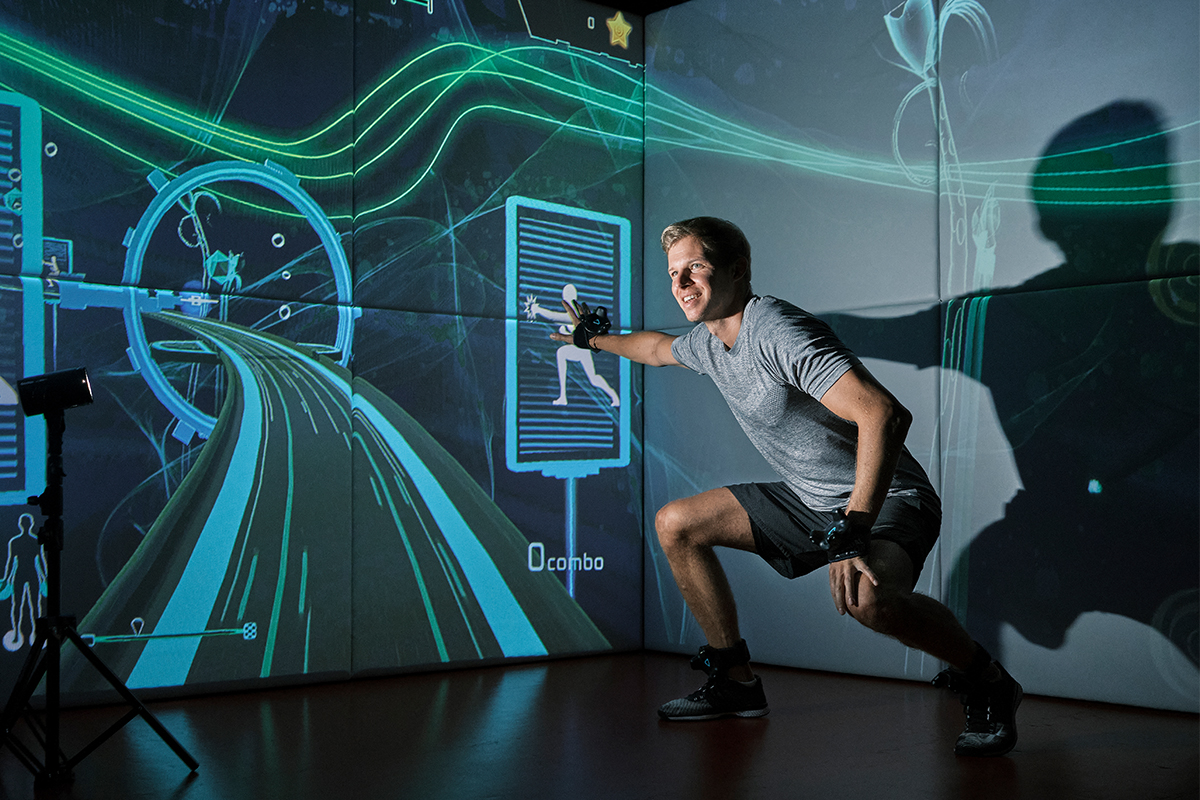

What is the focus of your current research?Among other things, I am currently investigating the effectiveness of exergames. These are interactive video games in which players control the game with bodily activity. For this project, we have set up an ExerCube in the lab. In this game, the test person is surrounded by three walls onto which we project a game scenario. During the game, the player navigates an avatar on a hoverboard along a virtual racetrack and while they are doing that, they have to carry out various motor-cognitive tasks for the avatar to overcome different obstacles. We measure what happens physiologically in this game and how the body reacts to that long term. If the training effect is as great as in endurance training, this type of physical activity would be an alternative for people who are not interested in conventional sports like jogging and keep-fit.

So you don’t only look into the performance of sportsmen and women?Not at all, I focus on children, older people, younger people, sporty people and couch potatoes. As a passionate sportsperson, I had to learn to be sensitive to the issues of the latter and also learn to accept that not everyone likes moving to keep fit. We do, however, incorporate sport science findings into the promotion of health and physical activity. As a scientist, it is important to me that my research results are relevant to practice and that you can derive something from them in terms of how to treat your body. That is where I see the value of my work.

Does the University of Bern give you the space to implement your ideas?I came to the University of Bern as a postdoctoral researcher in April 2020. I am relatively free to define my own research focus and am given support in my projects. Alongside my research, I also do some teaching. During the semester, this constitutes around half my workload

What do you particularly value about your area of research?I particularly like its interdisciplinary nature and the high practical relevance. Besides, I meet lots of different people through my work as I work with test persons. Sometimes, collecting data with the help of voluntary participants accounts for 40 percent of my work. This intense contact is unusual. In comparison to other subjects, we all have a friendly and relaxed attitude toward one another – like in sport, too.

As in other disciplines, too, research posts at universities are limited to a few years. And that makes your planning a little difficult. For the institutes it means that the researchers move on, with their knowledge, every few years. That means high staff turnover with a corresponding loss of know-how. This is a shame, particularly if you take the elaborate familiarization period into consideration.

How do you deal with setbacks in your career?I haven’t had to cope with any great failures but I have had to take a few smaller knocks, certainly: a project that just didn’t work or a paper that wasn’t published. And so I say to myself: “Get up and keep going.” With my experience in sport, I have learned how to deal with setbacks and how to grow stronger because of them. Besides, I don’t just work in research but also in teaching. So I can balance any setbacks in research that way.

They don’t hand out gold medals in research. But nonetheless: What would you say has been your greatest success?Here too, the sum of lots of small success stories is enough to keep me satisfied. I have always been lucky enough to find a research position. I know people I studied with who have now switched subject because their academic path came to an end. The fact that my choices worked is a success in itself.

Could you have imagined taking a different career path?I was interested in studying medicine, but the numerus clausus put paid to that. If I hadn’t studied sport science, I could well have gone into practice and worked as an athletics coach or a motion therapist. But looking back, I am very satisfied with my choice of profession. Because studying has to be fun. And I had fun studying and my work now in research really fulfills me.

Would you recommend your job to others?Both research and teaching are really exciting. But being a scientist is not always easy. Apart from the planning difficulties I mentioned earlier because of limited contracts, there aren’t all that many jobs for sport scientists, and the financing of projects is often uncertain.

How would you explain to a child what you do?We watch how muscles grow and how the heart works during sport.

About

Sascha Ketelhut

Since 2020, Dr. Sascha Ketelhut has been working as a postdoctoral researcher in the Health Sciences department at the Institute of Sport Science at the University of Bern. Contact: sascha.ketelhut@unibe.ch

New magazine uniFOKUS

Subscribe free of charge now!

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the new University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS shows what academia and science are capable of. Thematically, each issue focuses on one specialist area from different points of view and thus aims to bring together as much expertise and as many research results from scientists and other academics at the University of Bern as possible.