The advocate for puzzling astronomical objects

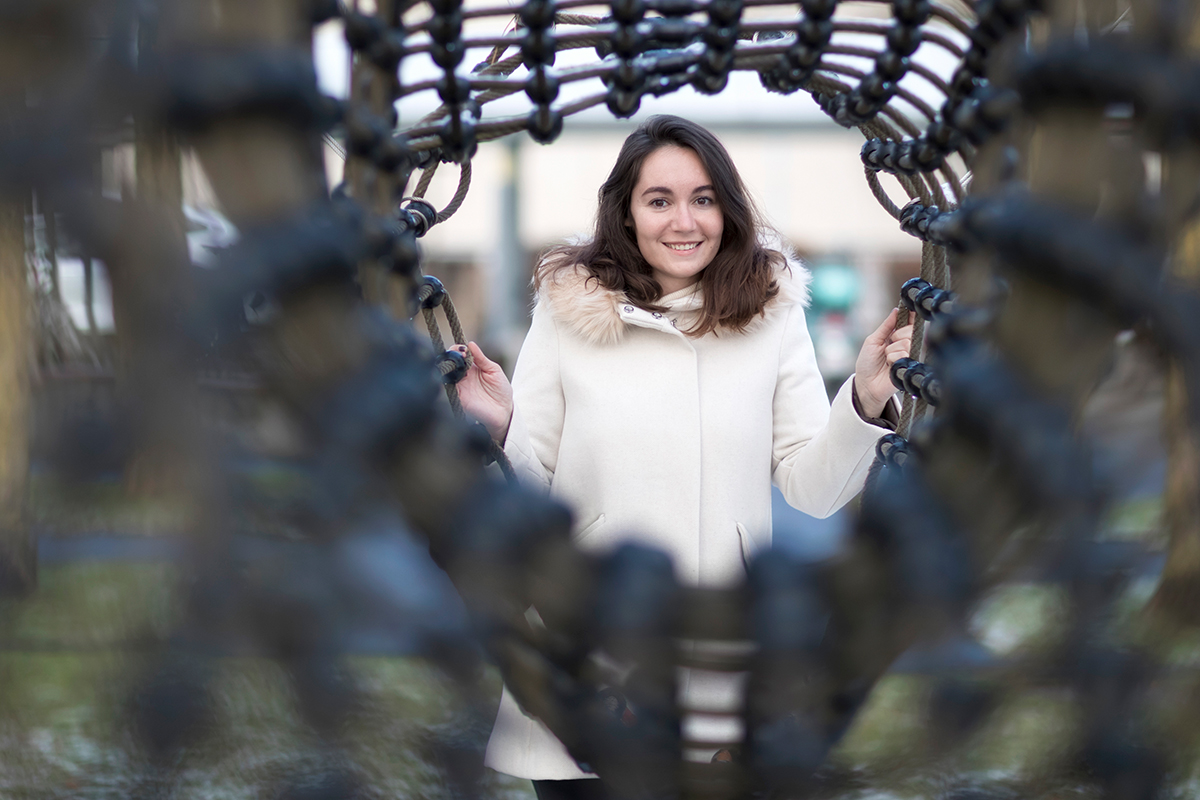

Brown dwarfs are puzzling astronomical objects that are heavier and hotter than planets, but lighter and colder than stars. A research team led by Clémence Fontanive from the University of Bern has recently directly imaged four new of these mysterious celestial bodies. In this interview, the astrophysicist explains why brown dwarfs are important to our understanding of stars and planets.

Clémence Fontanive: Actually, I had never heard of brown dwarfs before I applied for a PhD project about them. I got along with my supervisor instantly, and she really sold the project well to me. The more I learnt about these objects the more intriguing and fascinating I found them. Brown dwarfs are very weird objects, and I am definitely not going to run out of work if I keep on doing research about them. Every time we find a new brown dwarf, it raises new questions because every new discovery is as mysterious as the previous ones.

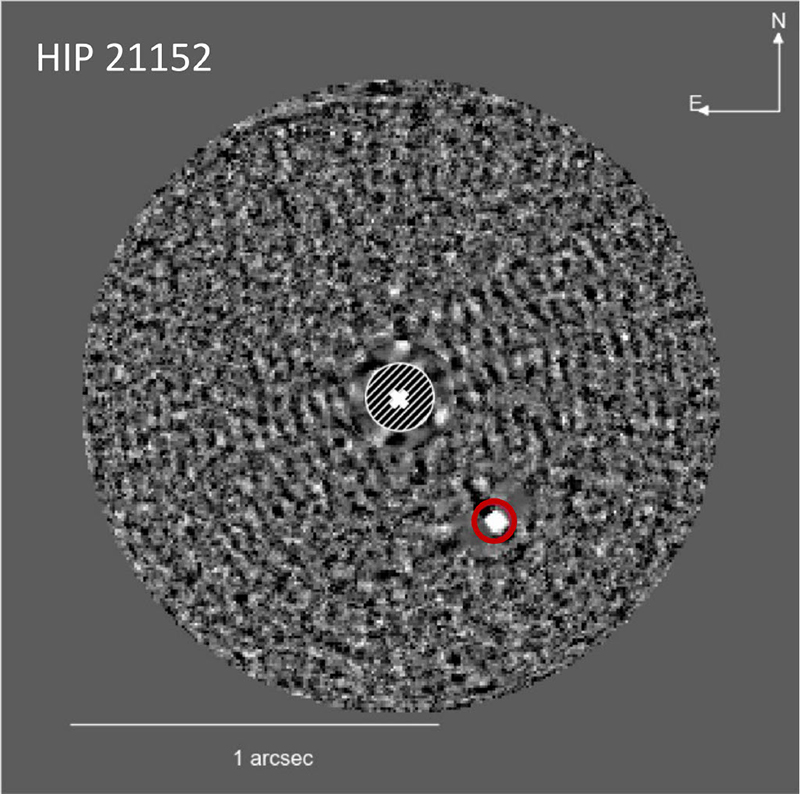

Can you elaborate on how big the discovery that you recently made is, of four new brown dwarfs around stars?99% of exoplanetary research is done indirectly, for example when researchers analyze the fraction of the light of a star that is diminished as a planet passes in front of that star. Instead, direct imaging allows us to take photos of giant planets or brown dwarfs themselves, which enables us to explore their atmospheres in great details. Unfortunately, it is hard to do, and only a few planets and about 40 brown dwarfs have been imaged directly around stars in almost three decades of searches. We developed a new search strategy which consisted in looking at only 25 carefully selected stars, which we had previously determined to likely have hidden companions. We could then image four new brown dwarfs by using ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, and these systems will be essential to study the formation and atmospheres of giant planets.

I don’t know if that is an official title, but it is a step forward definitely. We are not the only team doing this kind of research that preselects targets based on additional information from the ESA Gaia satellite. But we are the first ones to publish this as a complete survey, that is, we show exactly how many stars we were looking at and how many companions we found. And our results represent a major boost in detection rate compared to any previous imaging investigation in which researchers looked at stars randomly, with no such preselection.

There is a lot more research done on planets than on brown dwarfs.I definitely think brown dwarfs are underappreciated. We know roughly as many brown dwarfs as we know exoplanets: 4’000 to 5’000 brown dwarfs have been discovered so far if we count all those found through other methods and those floating alone in space. And the first discovery of a brown dwarf was actually announced in 1995 – which is in the same year and at the same conference that the first detection of an exoplanet was reported. Hence, there are these two big fields of exoplanets and brown dwarfs that have been growing in parallel as far as discoveries are concerned. However, for some reason everyone knows what a planet is, and exoplanets make the news all the time, while far fewer researchers study brown dwarfs, and most people have no idea what they are.

Do you think this is because we live on a planet and not on a brown dwarf? And why is research on brown dwarfs important?Brown dwarfs are everywhere in the Universe except in our own Solar System, so that’s clearly part of the problem. But brown dwarfs could be almost as frequent as stars, and in my opinion, they are equally interesting and equally valuable in terms of understanding both planet and star populations. The smallest brown dwarfs are comparable to giant planets orbiting stars and are often used to study planetary atmospheres since they are easier to detect, while the more massive ones are analogues to stars and may even harbor planets. If the models of formation and evolution for planets and stars cannot explain how brown dwarfs came into being, there is a problem with these models because we know that brown dwarfs come either from the same formation mechanisms as stars, or from the same processes as planets. It does not make sense to claim that we know where the Solar System comes from if the formation mechanisms explaining the origins of the Sun and planets, and other stars and exoplanetary systems, are not able to reproduce the observed populations of brown dwarfs as well. So, brown dwarfs are kind of a missing link that is needed to improve and validate what we know about both stars and planets. Because I don’t think they get the attention they deserve, I made myself an advocate for brown dwarfs, both within the scientific community and to the public.

I was already very curious about the Universe when I was a kid. I always wanted to understand how things work and needed an explanation for everything. My mind was always very science driven in that sense. And my dad always loved astronomy as an amateur, and he introduced me to it very early on. But it wasn't until I had started my studies that I thought of research as a career.

You recently published a funny and easy to understand Twitter thread about the paper in which you announced the detection of the four brown dwarfs. Why do you think it is important to promote science in social media?I joined Twitter two years ago when the last press release about a paper of mine was published. I think social media is an easy platform for science communication. It takes a bit of time to get followers, but the content is there for everyone to see it. For me, the main reason to be active on social media is to increase the visibility of women in science since they are still underrepresented. This is also why I didn’t consider a career in astronomy when I was young. I did not have any role models. All the scientists I saw were old men with beards. I hope that posting about science in social media encourages a few more girls to consider pursuing a career in science as an option for them.

MEDIA RELEASE

Ground-breaking number of brown dwarfs discovered

Brown dwarfs, mysterious objects that straddle the line between stars and planets, are essential to our understanding of both stellar and planetary populations. However, only 40 brown dwarfs could be imaged around stars in almost three decades of searches. An international team led by researchers from the Open University and the University of Bern directly imaged a remarkable four new brown dwarfs thanks to a new innovative search method.

About Clémence Fontanive

Clémence Fontanive has been an independent research Fellow at the Center for Space and Habitability of the University of Bern for the past three years. After studying Physics at Imperial College London in England, she completed a PhD in Astronomy at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, where she used ground- and space-based telescopes to understand the origins and characteristics of brown dwarfs and giant planets. As a postdoctoral Fellow in Bern, she has continued to explore the populations of brown dwarfs, both as rogue objects and as companions to stars, with a particular focus on developing new methods to improve our understanding of brown dwarfs and their connection to stars and planets. Since moving to Switzerland, she led a team that discovered an extreme system of two planet-like brown dwarfs in an unusual binary system, and successfully obtained observing time on the Hubble Space Telescope to measure the distances and study the atmospheres of the very coldest isolated brown dwarfs.

Contact:

Dr. Clémence Fontanive

Center for Space and Habitability (CSH) and NCCR PlanetS, University of Bern

T: +41 31 684 33 13

Email: clemence.fontanive@unibe.ch

BERNESE SPACE EXPLORATION: WITH THE WORLD’S ELITE SINCE THE FIRST MOON LANDING

When the second man, "Buzz" Aldrin, stepped out of the lunar module on July 21, 1969, the first task he did was to set up the Bernese Solar Wind Composition experiment (SWC) also known as the “solar wind sail” by planting it in the ground of the moon, even before the American flag. This experiment, which was planned, built and the results analyzed by Prof. Dr. Johannes Geiss and his team from the Physics Institute of the University of Bern, was the first great highlight in the history of Bernese space exploration.

Ever since Bernese space exploration has been among the world’s elite, and the University of Bern has been participating in space missions of the major space organizations, such as ESA, NASA, and JAXA. With CHEOPS the University of Bern shares responsibility with ESA for a whole mission. In addition, Bernese researchers are among the world leaders when it comes to models and simulations of the formation and development of planets.

The successful work of the Department of Space Research and Planetary Sciences (WP) from the Physics Institute of the University of Bern was consolidated by the foundation of a university competence center, the Center for Space and Habitability (CSH). The Swiss National Fund also awarded the University of Bern the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS, which it manages together with the University of Geneva.

About the author

Brigit Bucher is Head of Media Relations and the "Space" representative at the University of Bern Communication & Marketing Department.