Physics

His son’s smile and the call from NASA

Space scientist Andreas Riedo wants to find signs of life on Saturn’s icy moons. It is entirely probably that he won’t be able to achieve this ambitious goal himself within his professional career. And that’s why his research work always includes the promotion of early career researchers.

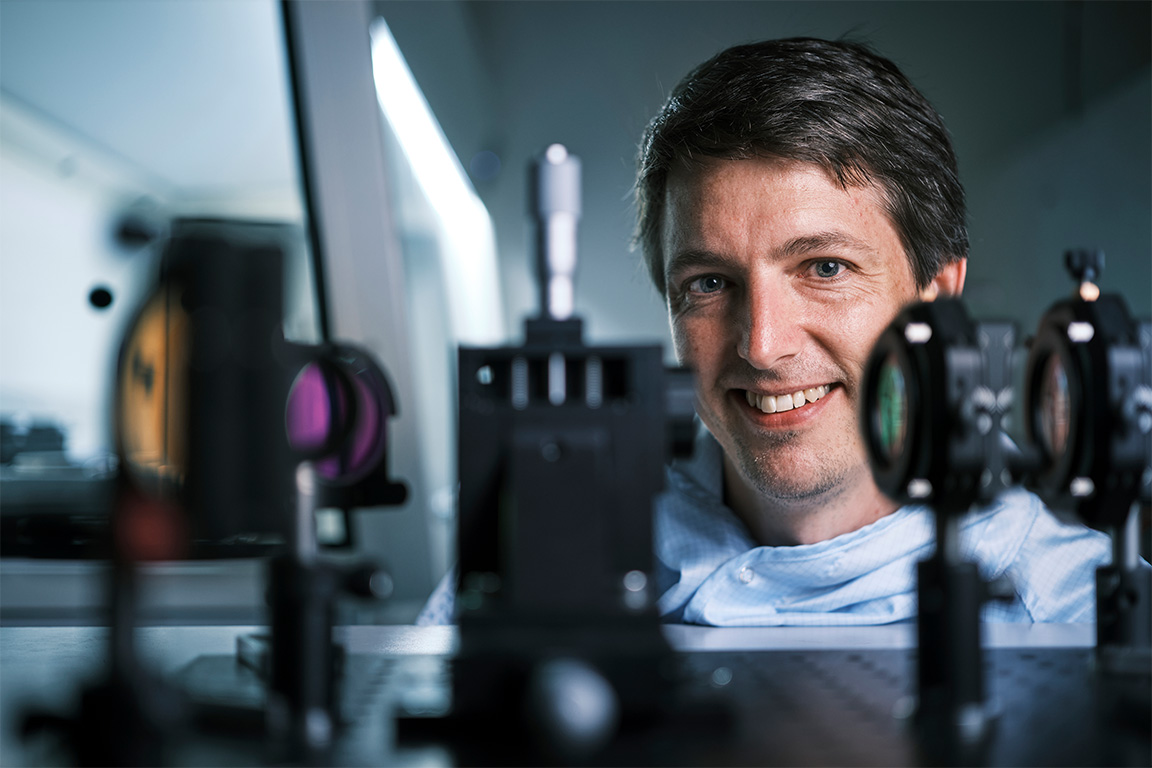

Time is on a completely different scale for Andreas Riedo. There isn’t a single clock on his office walls. The space scientist seizes opportunities as they present themselves, but plans years ahead of himself. He knows exactly the limited time slots in which he can send the instruments he and his team have developed on a mission. While the devices are often on their way to their research destination for years, he is already concocting the next project and has to convince sponsors and politicians of the coming research steps. And yet, Riedo still manages to find quite a lot of time for our interview. He appreciates contact to his fellow beings, whether bachelor students, a scientist, his young family or his friends. While at work he has to think a long way into the future, such interpersonal encounters bring him back to the here and now.

When asked how he would describe his work to his son, Riedo says that he would point to the sky at night. “I would say to my child: Look at the moon! When I’m at work I make devices that can determine what stones or particles of dust on the moon’s surface are made of.” And he adds that children have an incredible imagination and can sometimes understand complex things pretty easily. Like he did: as a child he had a wooden model of the solar system he made himself hanging from his ceiling.

Limits are there to be overcomeRiedo has been active in the field of space and planetary exploration since 2009. His work comprises the design, development and qualification of space instruments.

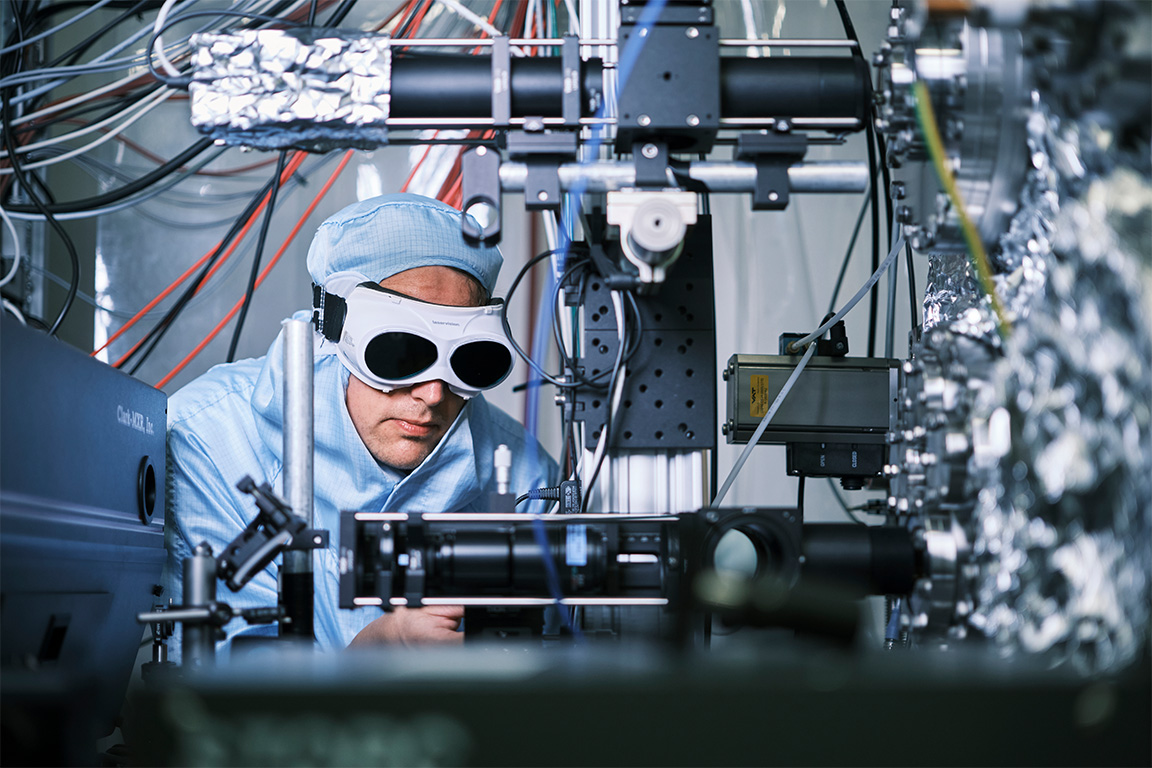

His interdisciplinary research team consists of specialists from biology, chemistry, physics, mechanics and electronics. With them, he spends time in the extremely well equipped lab at the Physics Institute at the University of Bern developing measuring devices that are to find traces of life on Saturn’s or Jupiter’s icy moons. To date, there are only conjectures about life outside of Earth, but no proof. However, water fountains from ice crevasses on the icy moons show that there is water under their kilometer-thick ice shells. Now it is a question of looking for primitive life forms such as microbes in this water. The 38-year-old has set himself an ambitious target to achieve.

”Our view of the world would change fundamentally if we knew there were other life forms somewhere other than on Earth. We would then know that life here on Earth is not unique.” It is in the very nature of natural science that it always has to continue researching: We discovered that the Earth is a globe and that several planets travel in orbit around the sun, man has been on the moon and we have even been able to land vehicles on Mars. Today’s technology makes all this possible. “The way I see it, my task as a scientist is to break further barriers. I start where we think we can’t go any further.” Riedo explains that he is looking for signs of life on the Saturn and Jupiter moons that we already know. He is specifically looking for organic molecules, such as lipids or amino acids which would indirectly point to life. “But who knows: Maybe we are already measuring traces of other life forms that we don’t actually know yet.” A striking statement which raises hopes of exciting findings.

Success is appreciationHe went to secondary school in the canton of Freiburg, where he got top grades in both physics and math. And that made his choice of subject at the University of Bern clear: physics. Space research in Bern is internationally highly recognized and an important European center, so it was an obvious choice for Riedo to stay at the University of Bern. He worked his way up the university structures, step by step, often on invitation because of his performance. This fall, he will defend his habilitation. “When I look back, I sometimes have the feeling that I have missed out on some of my youth.” When his friends were going out, he was often in the lab. But he was lucky: He had friends and family who always supported him and accepted his interests. “For me, major achievements are those moments when I sense a form of appreciation from those around me.” And that means that being greeted with a smile from his son when he gets home in the evening is just as important to him as the call from NASA telling him they are interested in his measuring instrument.

At the same time, Riedo also feels it is important to recognize other people's achievements too: His research would not be possible without his team. He works with specialists from all kinds of different areas and follows and greatly admires their work: “It is fabulous to watch how mechanics proudly and meticulously make complicated instrument parts.” It was only as he got older that he discovered he appreciates things made by hand. If he could go back to his youth and choose a profession again, he would perhaps train as a polymechanic or carpenter. But today he is a space scientist with every fiber of his being. “I’m in the right place here,” says Riedo, who is fulfilled by his work, which, at the same time, he counts as a hobby.

A lot of money that has to be used optimallyThe promotion of early career researchers is essential for space research. “Sometimes, a bachelor student actually comes up with an important element for my research in their dissertation,” says Riedo. He explains that scientists in his area always see themselves as part of a sequence of generations. “When we develop an instrument for a space mission, it can take up to ten years for it to be made. Then, on a mission for example to the Jupiter or Saturn moons, it can be on a journey of eight to ten years until it reaches its destination in space. I am now involved in a project which, even if everything runs smoothly, won’t actually get the first measurement data back to Earth until I am over 50.” And in some projects, he would almost be up to retirement age by the time results could be expected back. So he is faced early on with the question about who will continue his research. He needs a team with people coming through at the lower end of the age scale. That is the only way that science can work in his area.

Larger space missions can quickly cost more than a billion Swiss francs, so a far-sighted and responsible use of financial resources is imperative, says Riedo, adding: “In scientific disciplines, I think the attitude toward negative results should be improved.” Dead ends he feels should also be publicized. Others shouldn’t have to make the same mistakes and unnecessarily take up funding. “Unfortunately, it’s only success that counts in our areas. Straightforward career paths are often in demand. But that’s not right.” He feels showing the negative side of research will motivate others to improve the scientific approach. That’s exactly what happened to Riedo when, at the second time of asking, he was awarded the highly competitive Marie-Skłodowska-Curie scholarship that made it possible for him to complete a research stay in the Dutch town of Leiden. Besides, Riedo doesn’t feel that this success-oriented thinking reflects our existence. Because in the sciences, there are theories that life might just have happened by chance. And Riedo concludes the time slot he assigned our interview with a very interesting sentence: “This idea, that we may have been created by chance, is an immense help when it comes to having the courage to make mistakes.”

About

Andreas Riedo

Dr. Andreas Riedo is a researcher at the Physics Institute at the University of Bern in the Space Research and Planetary Sciences division. He designs and develops space instruments that are sent on NASA and ESA missions.

Contact: andreas.riedo@unibe.ch

New magazine uniFOKUS

Subscribe free of charge now!

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the new University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS shows what academia and science are capable of. Thematically, each issue focuses on one specialist area from different points of view and thus aims to bring together as much expertise and as many research results from scientists and other academics at the University of Bern as possible.