"Great potential is released by the interdisciplinary approach"

Matthias Erb and Andrew Macpherson are the coordinators of the new Interfaculty Research Cooperation (IRC) "One Health" by the University of Bern. In the interview with "uniaktuell" the professor of biotic interactions, and the professor of gastroenterology, explain how they want to decipher the connection between the health of plants, animals and humans with interdisciplinary research.

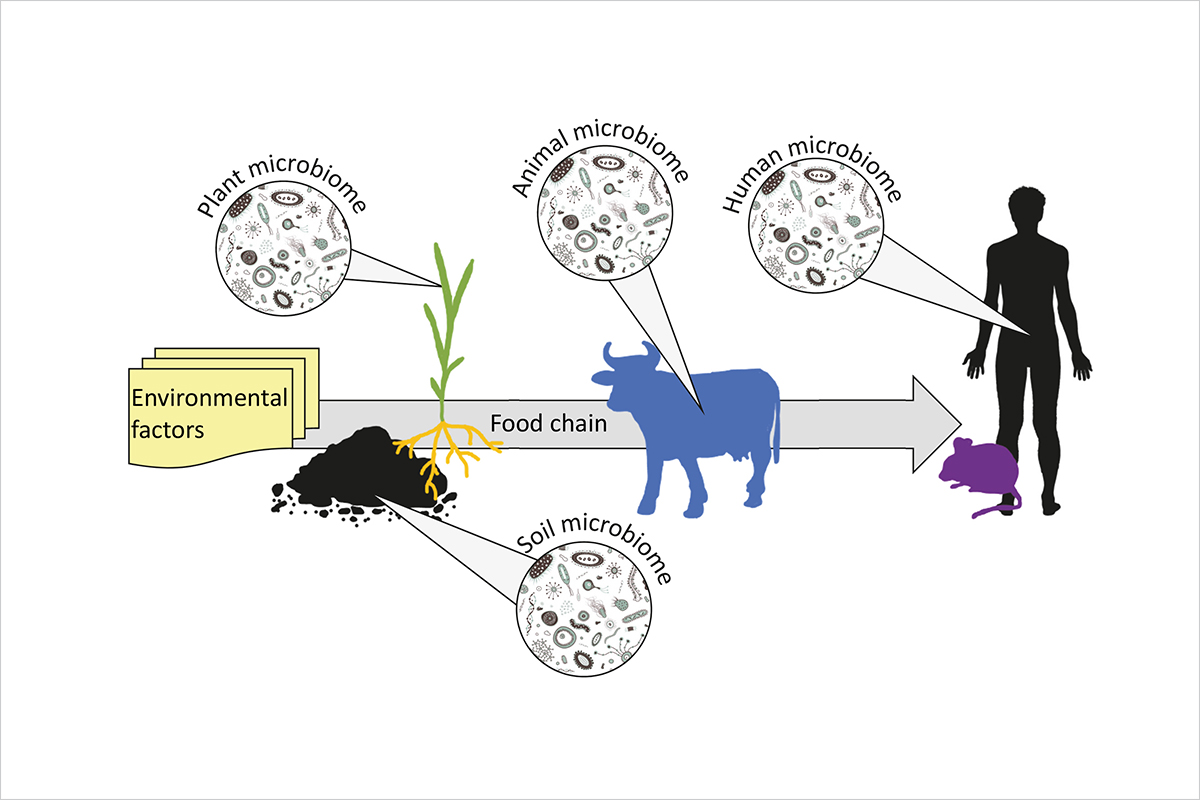

When environmental chemicals such as pesticides penetrate the soil, they can influence whole food chain systems – i.e. from soil to plants right up to ruminants and humans. This phenomenon is being investigated by the Interfaculty Research Cooperation "One Health: Cascading and Microbiome-Dependent Effects on Multitrophic Health" in nine research groups. The findings should contribute to better understand and improve the health of food chains.

"uniaktuell": What is new about your research question?

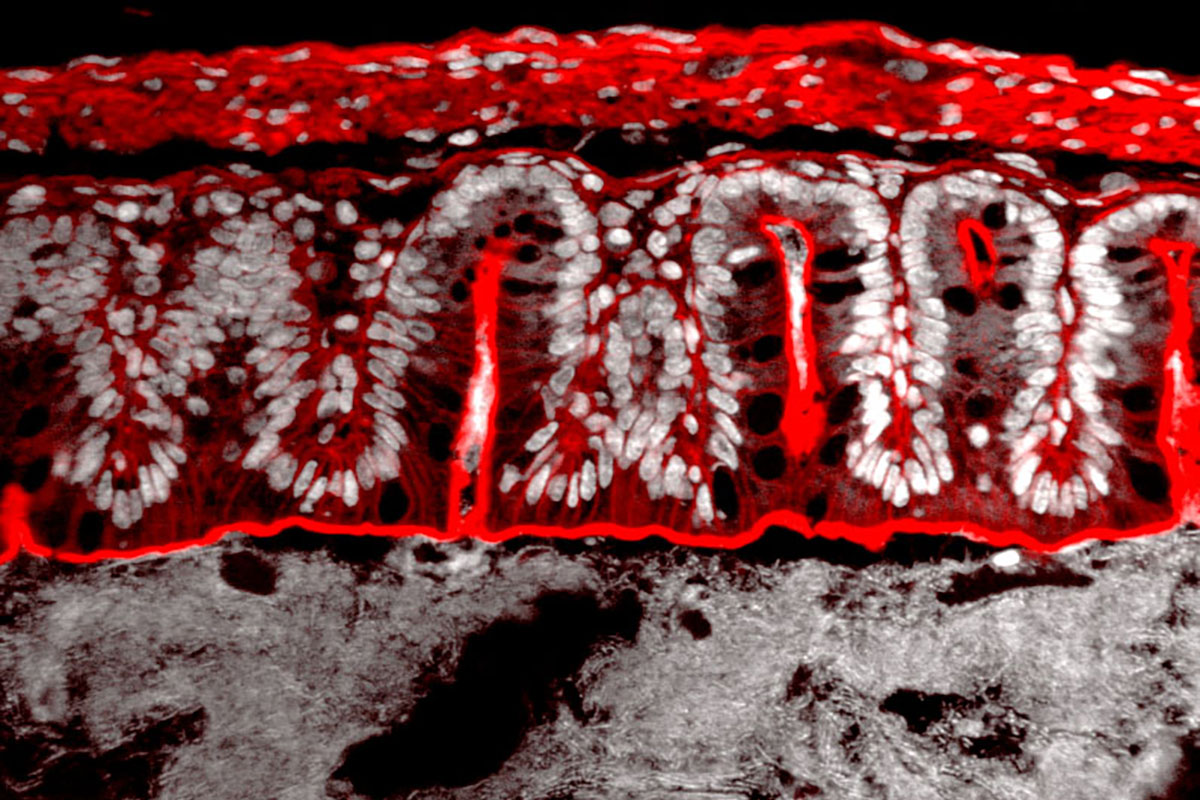

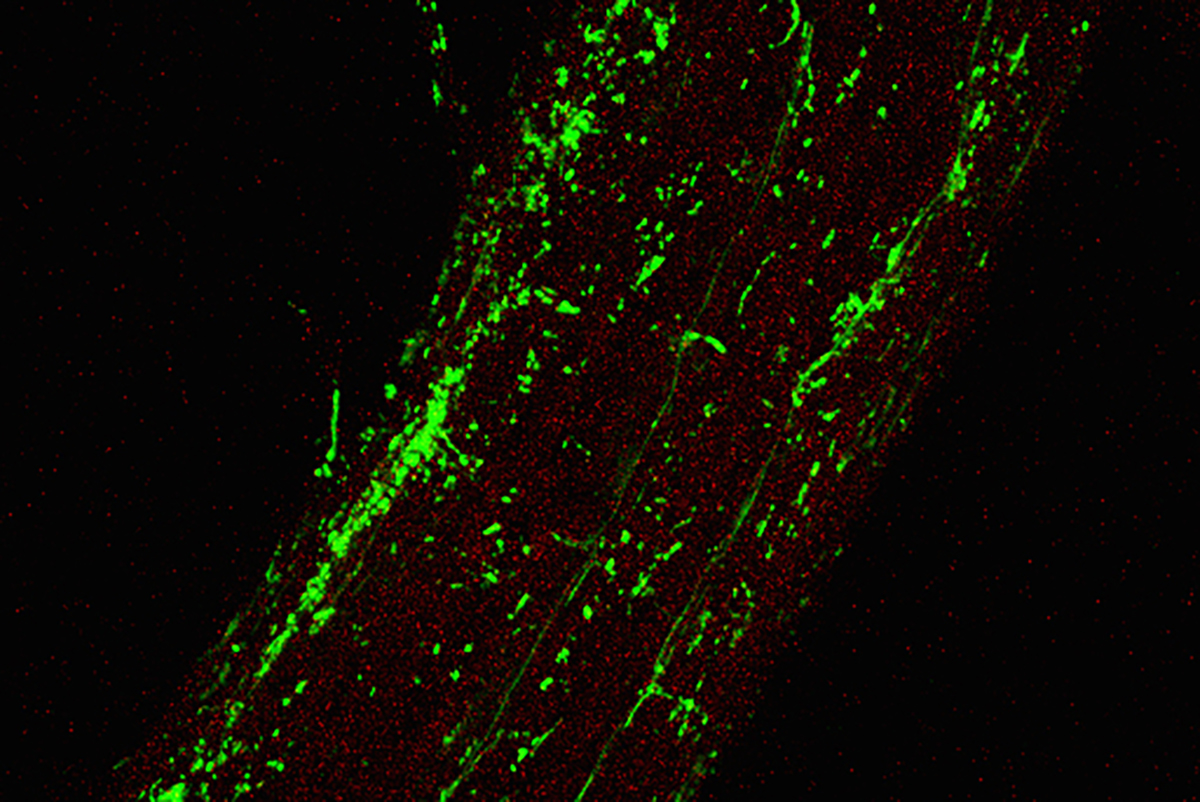

Matthias Erb and Andrew Macpherson: In the last few years, it was documented how much microbial communities influence the health of plants, animals and humans. However, until now hardly any research has been done into how these communities are influenced by environmental chemicals within a food chain and how these influences affect the health of the whole system.

Why can these questions only be answered in an interdisciplinary and/or interfaculty way?

To analyse food chains as a whole, we must know the biology of the individual links and the microbiome, and be able to study it. This is only possible by bringing together experts in soil, plant, animal and human health, with experienced environmental scientists, microbiologists and bioinformaticians.

How did you come to define your question?

Some of us already exchanged the first ideas on the topic of "One Health" in 2016, at a so called Town Hall Meeting at the University of Bern. A core group then met regularly, and worked on the main questions of the project. The unexpectedly great creative potential that was released by the interdisciplinary approach, was very motivating for us. And the end product convinced us all.

What exactly will the collaboration look like?

We will research the effects of three selected environmental factors – a plant toxin, a heavy metal and a pesticide – in detail. This will be carried out by several newly formed and networked interfaculty research teams, who will be supported by work groups on structured data analysis and food chain theory. When researchers from different faculties share test tubes and data tables, for us, that is the best proof of a successful collaboration.

Where are the challenges in interdisciplinary and/or interfaculty working in your specific question? What are the advantages?

The interfaculty work has been very positive so far; we dealt with the expected challenges early on, for example finding a common language, and developing a question, and thus were able to cope with them well. To us, the advantages of this research approach are obvious: We can understand systems and health contexts, which would otherwise remain a mystery. And we can benefit from each other in terms of methodology.

How would you describe the best possible result?

A better mechanistic understanding of the health of food chains, including the identification of the responsible microbial properties, would be the optimal result to us. That would lay the foundation for a better health of the whole system.

What benefits could your research results have for society?

The human influences on the environment have dramatically increased in the last hundred years. Therefore, important questions such as the following have arisen: Should the herbicide glyphosate be banned? Should maize monocultures be allowed in agriculture? Can we use microbial communities to absorb negative environmental impacts? Our work makes an important contribution to the future evaluation of these questions.

To what extent is your question oriented towards the strategy of the University of Bern, and what benefits can arise from your cooperation for the University of Bern?

By combining the expertise of three faculties, "One Health" links two priority topics of the University of Bern: health and medicine as well as sustainability. This means that for example, we will be able to strengthen the increasingly important microbiomics in Bern, by standardising experimental approaches and data analysis strategies. Our students and researchers are also trained interdisciplinarily, and therefore gain essential experience for their further careers. Last but not least, we hope to be able to contribute to further national and international profiling of the University of Bern with our new research ideas and results.

What are you most excited about with the interfaculty research cooperation?

In a half day discussion in our project consortium, we often learn more than in a three-day symposium. We are most excited about these intensive moments of joint knowledge gain and the subsequent Eureka experiences.

Matthias Erb

Matthias Erb has been an professor of biotic interactions, and co-director of the Institute of Plant Sciences since 2017. He grew up in the Bernese Oberland, and studied agricultural science at the ETH Zurich and Imperial College London. After his dissertation at the University of Neuenburg in 2009, he worked as a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow, and independent Group Leader at the Max-Planck-Institute of Chemical Ecology in Jena (Germany), before he was appointed Assistant Professor with Tenure Track at the Institute of Plant Sciences at the University of Bern in 2014. Matthias Erb researches the interactions between plants and plant consumers, on a molecular, chemical and ecological level. Thereby, biologically active plant active ingredients are the focus, which improve the pest resistance of wild and crop plants, and therefore make a contribution to sustainable farming.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Matthias Erb

University of Bern

Institute of Plant Sciences

Tel.: +41 31 631 86 68

matthias.erb@ips.unibe.ch

Andrew Macpherson

Andrew Macpherson has been a professor of gastroenterology at the University of Bern since 2008, and Director of the Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine at the Inselspital, Bern University Hospital. After his dual degree in medicine and biochemistry at the University of Cambridge (UK), he worked at various university hospitals, including King’s College Hospital in London. In 1997, he went to the University of Zurich, to work with the Nobel Prize laureate Rolf Zinkernagel, in the area of immunology. There, he developed methods to investigate the effects of intestinal bacteria on the immune system. From 2004 to 2008, Macpherson was an ordinary professor for gastroenterology at the McMaster University in Canada, before he moved to the University of Bern.

Contact

Prof. Dr. med. Andrew Macpherson

Department for BioMedical Research (DBMR), research group gastroenterology / mucosal immunology and Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Gastroenterology at the Inselspital, Bern University Hospital

Tel.: +41 31 632 80 25

andrew.macpherson@insel.ch

The Interfaculty Research Cooperations (IRC)

The Interfaculty Research Cooperations (IRC) With the Interfaculty Research Cooperations IRC, the University of Bern is launching joint projects, each of which involves 8 to 12 research groups and which are being specifically funded. At least two faculties must be involved in each IRC. Three projects have now been approved in a competitive process.

The IRCs are targeting their research on the five strategic areas of focus of the University of Bern, according to the strategy 2021: Health and medicine, Sustainability, Politics and administration, Matter and the universe as well as Intercultural knowledge. The research cooperations are each funded for four years with 1.5 million Swiss francs per year. The IRCs are based on the subject focuses of the National Centers of Competence in Research (NCCR) of the Swiss National Science Foundation.

About the author

Ivo Schmucki is an editor in Corporate Communication at the University of Bern.