"Nobel laureate Kocher was certainly not afraid to rock the boat"

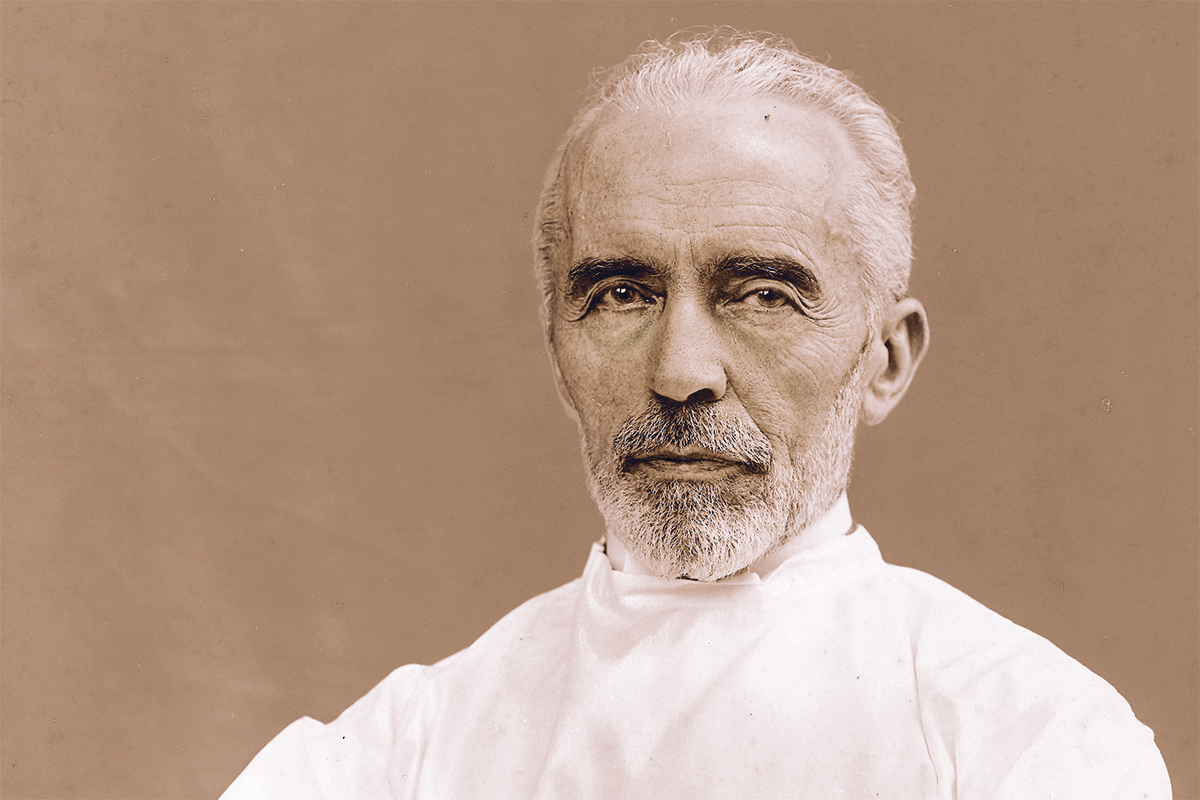

Theodor Kocher (1841-1917) is seen as a trailblazer for modern surgery, and engaged in pioneering work in many different fields of medicine. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1909 for his work on the thyroid gland – and was the first surgeon and the first Swiss medical doctor to receive the Prize. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Kocher's death, uniaktuell spoke to Vice-Rector Daniel Candinas, the current incumbent of the chair once held by Theodor Kocher at the University of Bern.

"uniaktuell": Professor Candinas, you currently hold the chair once held by Theodor Kocher. What was your first encounter with Theodor Kocher?

My first encounter with Theodor Kocher was in the 1980s when I was studying medicine in "far-off" Zurich: Kocher's name was repeatedly mentioned by professors in surgery lectures in a wide range of contexts. I can no longer recall all the details, but I clearly remember that his achievements were recounted not just with awe and respect, but also with a certain pride. In Zurich, Kocher was "the Swiss Nobel laureate", "the Swiss surgeon", the "systematic Swiss hard worker", the "Swiss pioneer of surgery". The fact that Kocher came from and worked in Bern, and that Bern provided the environment and platform for that work, was of secondary importance. I must admit that I only began to explore the links between Kocher, the University of Bern and the Inselspital when I took up my post here.

And when you came to Bern?

I worked for a number of years in Birmingham (UK) before my appointment in Bern, and my colleagues there talked to me about the great pioneers of surgery who had worked at Bern University Hospital: Theodor Kocher, Fritz de Quervain and Leslie Blumgart were all respected historical figures amongst my English colleagues, and for me an added incentive to give my very best in Bern. Things then came into focus in February 2002 shortly after I took up my post. My secretary at the time came to me in a state of some consternation to report that my predecessor had had the original portrait of Kocher from the chief surgeon’s office packed up and sent to Heidelberg with him. She later travelled to Germany in person and returned with great pride with a small parcel, since when the picture has once again hung in its old place in my office.

Theodor Kocher is seen as a trailblazer for modern surgery and engaged in pioneering work in many different fields of medicine. You once wrote in an article that gaining control of key elements such as anatomy, physiology and adverse reactions to operations was at the center of innovations and new developments in medicine. Could you illustrate this point using the example of Theodor Kocher?

Even if many operations now seem routine, we must not forget that although the human body has a huge potential for self-healing, nature still did not intend entire parts of that body to be manipulated, changed, removed or indeed replaced. To make such procedures possible, we need to find systematic ways to apply nature's rules so effectively that operations – external physical intervention – can be conducted in safe conditions. The medical historian Thomas Schlich proposed "control theory" (Kontrolltheorie) as a way to understand the stages in the development of medicine. From this perspective, Kocher's achievements could also be understood as a system for improving control in the "death zone" of surgery. Kocher lived at a time of unprecedented change and upheaval. The new was open to all those who sought with intelligence and hard work to shake off the burden of a previous era. Many of medicine's all-embracing theoretical constructs with no empirical basis, some of which dated back to Antiquity, were coming crashing down. At the same time, new findings from chemistry, physics, biology and above all hygiene and engineering for apparatus design were emerging at considerable speed in a world that already had the tools of a global communication culture. Surgery itself has for centuries been excluded from the circle of noble academic disciplines; in fact, in 1163 at the Council of Tours, the dangerous nature of the profession led to Pope Alexander III ("ecclesia abhorret a sanguine", "the Church abhors blood") "exiling" it into the premises of barbers and barber-surgeons, who practised surgery like a trade with varying degrees of skill.

How did Kocher help to bring this "surgical trade" into the field of science?

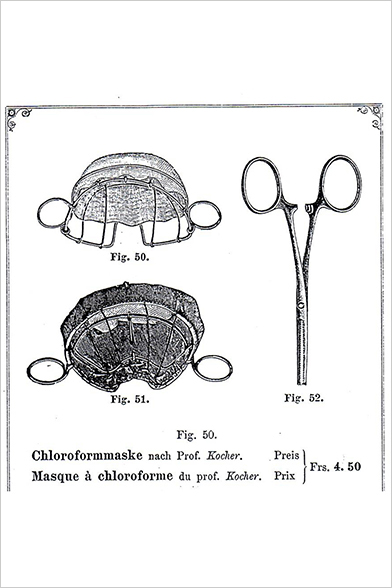

With the introduction of anaesthesia in the mid-19th century and the discovery that the much-feared postoperative gangrene could be avoided, at least in part, by taking hygiene precautions, the way was open for development in surgery. Kocher engaged in painstaking research into the effects of various surgical procedures on postoperative results, seeking to determine the causal links. Although it was only his successor, Fritz de Quervain, who researched using modern statistical methods and control groups, Kocher established the systematic observation of post-operative processes and kept detailed records of possible factors that he believed had a significant impact on results. For example, he made systematic observations on the side effects of various anaesthetic procedures, on which basis he then developed recommendations for various different indicators and groups of patients. One conclusion he reached was that the then frequent and dangerous goitre operations were best conducted under local anaesthetic. Key to Kocher's understanding of medicine were his experiments on animals, which he carried out with great assiduity throughout his career. Initially financed in part by the fortune of his mother-in-law, he experimented on the coagulation system, intracranial pressure, epilepsy, the effect of bullet impact and the physiology of the thyroid, to list just a few of his areas of work.

How significant was Theodor Kocher for the Inselspital during his lifetime, and how important is he today?

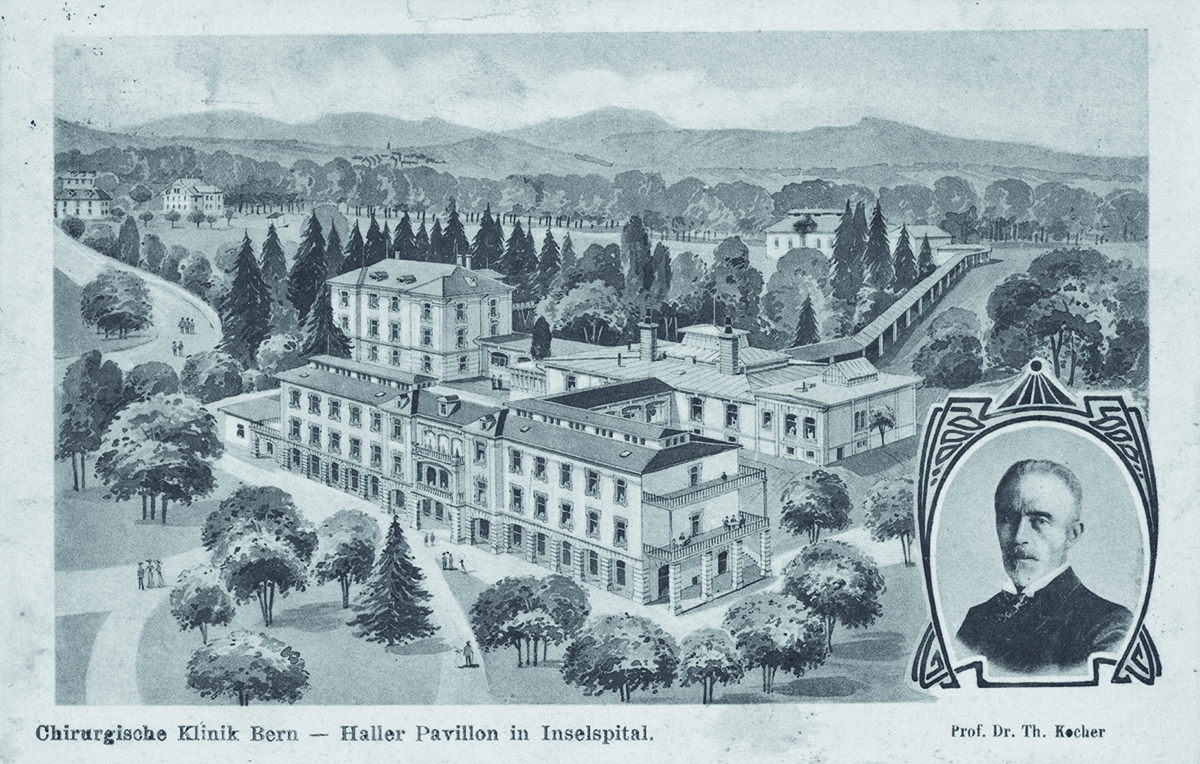

The former of Head of the Inselspital, Fritz Leu – himself an outstanding visionary figure and a great asset to the hospital – explored precisely that question in an article published in 1991 in a monograph on Kocher edited by Urs Boschung. That article explains that Theodor Kocher was a prominent promoter of the new University Hospital building in Kreuzmatte (where it still stands today), investing his own funds and raising donations in a campaign organised primarily by his spouse Marie (nee Witschi), and exerting his influence as Rector of the University of Bern. To get his own impression of modern hospital architecture, Kocher travelled halfway across Europe to inspect around a dozen examples in the company of the architect Schneider. Conditions at the old university hospital in the grounds of what is now the Federal Ministery of Interior were intolerable for both patients and staff in terms of infrastructure, space and sanitary facilities. Politicians had long debated how best to deal with the situation. The cheapest option for a new building had been costed at around 2.1 million francs, and this was seen as not politically feasible. Through various financial arrangements, sales of land and a number of other measures in which Kocher was actively involved, a package of 700,000 francs was finally put together and passed with a large majority by both the Grand Council and the voting population in November 1880. To me, there are two significant points here for later generations and for the collective identity of the Inselspital. Firstly, the Inselspital, founded with money bequeathed by wealthy widow Anna Seiler in 1354, was originally established as a hospital for the needy to provide beds "for thirteen bedridden persons, cared for by three honourable persons" and retained this status as a hospital for the poor for some time, even when it moved to Kreuzmatte, where 320 beds were available. Wealthy patients were treated elsewhere, including by Theodor Kocher himself, who had built his own private hospital – operations were even known to have been carried out in the dining room of a fine hotel. The transformation into the University Hospital did not happen until later, although Kocher increasingly used the new building de facto as a university hospital for teaching and research. Secondly, even during Kocher's time, there was a debate on the relationship between healthcare service provision, teaching and research. The statutes of 1898 give prominent mention to the facility for the poor, whose main purpose is treating needy patients. The "facility for the education of doctors in training" is only of secondary importance.

Kocher was without a doubt also key as a scientist, physician and rector in shaping the University Hospital, and he also engaged in philanthropic work. Take for example the 200,000 francs that he donated to science for "research into human processes in the broadest sense" ("Erforschung der Lebensvorgänge im weitesten Sinne") – which according to Tröhler's research correspond to the prize money for the Nobel Prize at the krona to Swiss franc exchange rate at the time. This money was later to lead to the establishment of the Theodor Kocher Institute, and also funds the annual Theodor Kocher Prize.

How did surgery at the University of Bern and Bern University Hospital continue to develop?

The former surgical department in the new University Hospital in Kreuzmatte opened in 1884 was in Haller-Haus, a separate complex built in the pavilion style. Kocher practised what is from today's perspective a huge range of surgical procedures, and brought significant innovations to everyday clinical work in all fields of practice of the time. Here is just a brief selection as an illustration: in limb surgery, he developed new procedures for treating fractured hips, and new methods for reducing dislocated shoulders. In gastrointestinal tract and endocrine surgery, he demonstrated his brilliance with optimised concepts for thyroid operations and new procedures for mobilising the duodenum in stomach operations, improved the technique for tumour operations in the lesser pelvis and conducted tissue transplant experiments. In neurosurgery, he explored the problem of intracranial pressure and searched for solutions – with the help of a young American surgeon, Harvey Cushing, who was there on an extended visit. He is nowadays considered one of the fathers of modern neurosurgery. The ear, nose and throat and the eye department already operated separately from surgery in Kocher's day. The further division of surgery into the many organ-specific specialities that we are familiar with today came much later, and was a gradual process. In 1963, Maurice Müller became Professor of Orthopaedics, and with the retirement of Karl Lenggenhager, who was Professor of Surgery at the University of Bern from 1942 until 1971, greater specialisation was also reflected in the top University staff. Lenggenhager's successor, Rudolf Berchtold, was a GI tract and endocrine specialist in the modern sense of the terms; Ernst Zingg became Professor of Urology and Ulrich Althaus Professor of Heart Surgery, to name just a few examples. Even within the field of GI tract and endocrine surgery, specialisation in individual organs has increased. In my department alone, there are now eight "organ" teams who carry out the most complex surgical procedures on and engage in their own research into the thyroid, pancreas, the liver, the rectum et cetera. With the recent appointment of Guido Beldi as Professor of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Vanessa Banz as Head of Transplant Surgery, the next generation is now also ready to approach the challenges of the future.

What is the current status of medical and medical technology development in Bern? Is the Bern success story continuing?

Success is defined in terms of the competition and depends not just on individual creativity and excellence, but also – as in Kocher's time too – on location factors. If we study the political environment of the time through quotes and records, we can see that the same issues were dominating discussions then as are now. Kocher was a medical and scientific figure with strong ties to Bernese society; a figure whom administrators and politicians could only treat with respect even when his views appeared absolute and sometimes inconvenient. He was certainly not afraid to rock the boat, unlike certain business-minded hospital managers' ideal chief medical staff today. Kocher brought together an effective combination of creativity, hard work and strong local ties – and these last were perhaps more important in traditional Bern than in cities with greater industrial migration. That combination was a model for success, and laid strong foundations for Bern's lasting renown in the field of medicine. Kocher was instrumental in creating lasting structures that have also helped later generations succeed – Hans Goldmann in ophthalmology, Maurice Müller in orthopaedics, Fritz de Quervain and Leslie Blumgart in GI tract and endocrine surgery, Ewald Weibel in physiology, Marco Mumenthaler in neurology and Urs Studer in urology, Bernhard Meier in cardiology are just a few figures from Bern's medical faculty who have become world-famous and in turn made significant contributions to Bern's development and links as a center of medicine.

What do you see as the strengths of and future challenges for medicine in Bern?

Firstly, I firmly believe that one day, on the occasion of a future anniversary and another look back at the faculty's history, we will also be listing the names of female colleagues. Today the current staff at the faculty is welcoming more and more brilliant female doctors and scientists. I have only named a few previous members of staff here. They are simply a representative sample of the many who have contributed to Bern's success in medicine and continue to do so today with energy and commitment day after day. It would, however, be presumptuous to judge the achievements of the current generation. Instead, let me just highlight a few facts: we are on the way to becoming Switzerland's largest medical faculty, and the Inselspital leads the field in many areas, in particular in highly specialised medicine. What is more, the partnership between the University hospital and several district general hospitals is unique in Switzerland and offers opportunities that we will hopefully be able to harness in the future also for academic purposes. It seems to me that the tide has also turned at a political level in favour of strengthening Bern as a center of medicine. Yet political will, sharp brains and a large student intake in medicine are not enough on their own. In this complex environment, we also need greater coordination between the different players in academic medicine – and in addition to current research initiatives (such as ARTORG and sitem-insel), we need more, broad structural projects to further diversify Bern as a center of medicine. Computing at the interface between biology and medicine (big data), digital image processing and smart medical communication systems are just some examples of where we should be investing more in future. In Kocher's era, one leading figure could influence an entire system. In these times of globalised and digitalised cooperations, structural issues, flexibility and investment in the fields of the future are the major overarching challenges. We must also consider the speed at which changes are taking hold and turning entire fields of medicine upside down.

THEODOR KOCHER

Theodor Kocher was born in Bern on 23 August 1841. At the age of 17, he enrolled as a medical student at the University of Bern. After obtaining his doctorate, he spent time studying in Berlin, London and Paris, where he established contact with prominent doctors and familiarised himself with the latest development in medicine. Kocher developed a new method for shoulder reduction (the "Kocher method") that brought him immediate fame. In 1872, aged 31, he was appointed Professor of Surgery at the University of Bern. His pioneering work in various different fields established his global reputation, for example on surgical techniques (goiter surgery and the development of the "Kocher manoeuvre" for operations in the upper gastrointestinal tract), on the development of medical instruments (including the Kocher forceps named after him), on trailblazing developments in the treatment of wounds, and on the establishment of a school of surgery at Bern University Hospital. In 1909, Kocher became the first surgeon and first Swiss medical professional to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine. The Prize was awarded for his research into the thyroid. In 1912, on the occasion of 40 years of service at the University of Bern, Kocher donated 200,000 francs to the University. Since 1915, this money has enabled the annual award of the Theodor Kocher Prize to outstanding young researchers, and led in 1950 to the foundation of the Theodor Kocher Institute. Despite many offers from abroad, Kocher remained faithful to Bern until his death in 1917. Kochergasse, Kocherpark and a bust in front of Bern University Hospital commemorate the pioneer in Bern today.

DANIEL CANDINAS

Prof. Dr. med. Daniel Candinas has been Vice-Rector for Research at the University of Bern since 2016 and Professor of Surgery specialising in abdominal surgery and Director of the Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine at Inselspital, Bern University Hospital for 16 years. He previously worked in Birmingham (UK), Boston (USA) and Zurich, where he also studied and qualified as a professor. Together with the hepatologist (liver specialist) Jürg Reichen and the gastroenterologist Andrew Macpherson, the 56-year-old from the Grisons founded the first interdisciplinary university Unit in Switzerland and expanded the Abdominal Center Bern. As a surgeon, his main specialities are liver and pancreatic surgery and liver transplants. His research focus is in liver cell biology, where he and Deborah Stroka are investigating the underlying mechanisms of liver regeneration and tumour development, and in the development and introduction of computer-assisted navigation systems in surgery. In the latter area, he collaborates closely with the working group headed by Stefan Weber from ARTORG.

Contact

Prof. Dr. med. Daniel Candinas

Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Visceral and Transplant Surgery

Inselspital, Bern University Hospital

3010 Bern

Direct line: +41 31 632 24 04

E-mail: daniel.candinas@insel.ch

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brigit Bucher works as the Deputy Head of Corporate Communication at the University of Bern and is the Editor of "uniaktuell".